Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

Today, I’m talking to Jamal Shahin from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel about the project PARENT. He wastes no time in clarifying that he’s not an academic studying child rearing. Jamal’s primary interests are how stakeholders or different actors can get involved in decision making in the political sphere. PARENT is an acronym which means “Participatory Energy Management System.” Great I think, I’m glad this won’t be a forty-minute discussion about how your kids go wrong.

Yet I still have no idea what a “Participatory Energy Management System” is, and I am not quite ready to admit it yet. Thankfully, Jamal begins by taking the lead and talking about the inception of the project, “one of my fields of interest has always been the relationship between technology and participation, how do people use technology to enhance their participation?”

Jamal provides context by referring to the dot com boom: back then everyone was convinced that the internet was not only going to transform business but was going to radically reshape society itself. I think to myself, I can order pizza easier via an app and I can get an uber, so the business side checks out, however, I’ve never thought about the society bit. Jamal says, “eighteen years later and we’re still talking about how technology influences policy making and influences participation, and we’re using the moniker the smart city to describe this.

Jamal explains that the PARENT project emerged from three different concerns: the first of these was environmental sustainability, the second was technology and its role in society, and the third was how participation plays a part in the first two. He says that these three prongs are the main issues the PARENT project addresses. Jamal then throws out a question, “what can technology do to engage citizens in developing a more sustainable future for their city?”

This is clearly a massive question to answer, so I am glad he doesn’t actually expect me to answer it. In the split second I have to wait, I think there are many possible answers. Jamal answers that PARENT focuses on one: the issue of household energy consumption. I ask why household energy consumption? He responds, “we thought this is one area where we could actually have an impact on individual citizens, and we could build up a community that actually wanted to actively participate in this.” This is starting to make sense to me, after all, big ideas have to be scalable. Then Jamal jumps in to say, “we were also aware there is this emergence in domotics”. Domotics?

I have a hazy feeling that domotics has something to do with ancient Greek, so I am starting to feel lost again. Jamal thankfully goes on to define it precisely, “domotics is different technologies and how they play a role in the household.” Okay, so I guess I was off with ancient Greek. He elaborates by saying demotics could be classed as smart technologies connected to the internet or they could be smart technologies that are more bound to the household. In either case, they provide detailed information for the user. I feel much clearer on the concept now: I tell Jamal it’s like Fitbits for homes. He responds, “indeed, Fitbit represents one side of this: collecting information and presenting that to the individual. The other side is building up larger data sets from a community of users.”

Jamal says both sides of domotics are represented in the PARENT project. He states, “not only have citizens used the technology we’ve provided to inform themselves, but we’ve also been able to use the data they’ve provided us to gather global summaries of what is going on in their region.”

I then learn that the project installed energy monitors in households in three cities, driven by the PARENT consortium: Brussels, Bergen, and Amsterdam. These monitors track the individual household’s electricity consumption twenty-four hours a day. The data is then gathered by the monitors and uploaded online to the PARENT platform. This allows households to see how their energy consumption compares to their wider community. This data not only tells individuals how much energy is being used but also when it is being used.

When considering what the PARENT project offers compared to how people normally see their energy consumption, I feel a bit jealous. Usually, people get their energy bills at the end of the year, so it’s difficult for them to make the connection between reducing their energy consumption and reducing their bill, this project tackles this problem head on. Jamal tells me the monitoring of electricity usage is precise enough to see what happened down to five-minute intervals. This all starts sounding like a lot of data to me. The platform that participants can use, allows households to compare their energy consumption against others with similar housing situation. Before, I could even ask about complexities, Jamal pre-emptively says, “we had a few challenges installing the technology because it requires accesses to people’s fuse boxes. Also, we had challenges with getting people to connect their devices to our platform.”

I wanted to take a step back, what I didn’t understand yet was why Brussels, Bergen, and Amsterdam? It turns out that the Vrije Universteit Brussel works with the Universities of Bergen and Utrecht and Blue Planet in Brussels and Resourcefully in Amsterdam, two organisations with specific expertise in energy management. Jamal explains that these three cities have very different energy needs and therefore allow the project to test different scenarios for which our respective partners have expertise. For example, in Norway energy consumption is a lot less of a concern because electricity is cheap and it is generated through hydroelectric systems, therefore there isn’t such an emphasis on consumption efficiency. Amsterdam allows for the possibility to create a community of prosumers (producers and consumers); this is due to the fact that many people live on house boats with solar panels. Finally, in Brussels they have carried out joint activities with two of the local municipalities, focusing on awareness and participation. I think, woah! this project certainly has a lot of different ways of looking at electricity consumption.

In particular, I find the Brussels case interesting. I say to Jamal, “if I understand it, in the Brussels case you have two key aims: one is making citizens more aware of their energy consumption and the second is to make them more engaged in reducing their energy consumption through participation.” Jamal tells me I’ve nailed it. This makes me feel a bit smug for a moment, but I feel like I still need a bit more detail, however yet again Jamal anticipates the questions to follow.

Jamal tells me that in the Brussels case, the team systematically sent out newsletter every two or three weeks to the community of participants, and they also organised several workshops for the participants so they could share their experiences. These workshops let citizens engage with different civil society actors and exchange important information. Jamal says, “we were trying to build synergies between all the different activities that take place.” He goes on to explain, the aim of this was to create a space for citizens to interact, so they could be properly informed about how their energy consumption looked on both an individual and communal level.

So far, I understand the benefits of having a better idea of knowing your personal energy consumption, but I am still bit perplexed how community comes into all of this. Jamal addresses this swiftly, “it’s about addressing the challenge of global climate change, people are asking what this means for us?” He highlights how there is genuine concern from people about this issue. He tells me that in Brussels there are lots of groups interested about the behavioural changes necessary to address climate change. PARENT aims to help people make these behavioural changes.

I am genuinely surprised and inspired to hear that change is being sought from the grassroots as opposed to being dictated from above. I wonder how the project manages to harness and amplify this grassroots interest. I ask if there is an element of gamification at play? Jamal says, “I wouldn’t say gamification, but I would say incentivisation.” Okay then, I thought, how are people incentivised? He enthusiastically brings us back to the Fitbit analogy, “when I first got mine it told me how much I wasn’t doing, three weeks later it was in the bottom of my drawer because it kept telling me how much I wasn’t doing.” I look at my own health tracker, then look at my less than perfect physique and then laugh along with Jamal. He follows this up with something which strikes me as an important thought, “technology provides information, but it doesn’t provide motivation.”

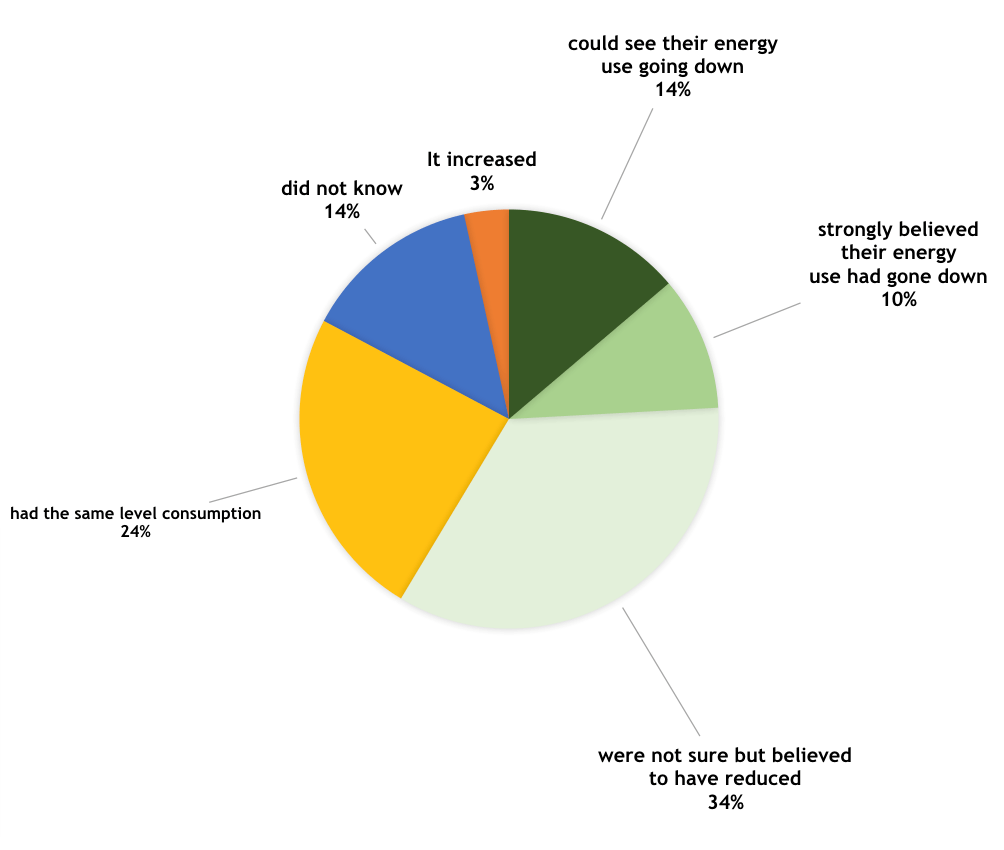

Now I am really curious to hear what Jamal is going to say next. He explains that the PARENT project really emphasises the human aspect of behavioural change, without this the motivation bit wouldn’t be possible. The project focuses on motivation in a number of ways: leader boards have been created to add an element of competition, people have been given the opportunity to self-identify what kind of energy consumer they are, community workshops have been held, and prizes have actually been given out for good consumption decisions. Talking about the newsletter again, Jamal explains that it was more than just an update document, it sought to provide the guidance needed to change behaviour. Jamal stresses the importance of understanding what motivates people. He tells me, you have to comprehend the fact that different people are motivated by different things, which can’t be done without a human touch.

Jamal tells me that PARENT identified two different but equally strong motivations within the Brussels community, the first was the desire the do something genuinely helpful to reduce climate change and the second was simply to reduce household energy consumption. Of course, for some people both objectives were equally important. Nevertheless, Jamal makes the point that PARENT has to appeal to different parts of the community in order to work.

Feeling much more confident in my comprehension of the project, I remember we were talking about the PARENT platform itself before I side-tracked the conversation. Thankfully, Jamal threads it all back together quite gracefully, he talks about how these human elements were considered alongside the technical challenges when setting up the platform. He has already explained the technical issues around installation. However, now he wants to talk about the issue of trust. He explains that in Brussels, “because we were a public research project, they trusted us implicitly.” Whilst in Amsterdam, there had been debates about the use of smart meter data, which meant people initially had a lot more questions about security. I guess it is important to build trust, Afterall, the PARENT platform does gather a huge amount of household data.

This brings up a question quite naturally: I ask, “How did you persuade people to trust the platform?” Jamal says that “we carried out all of our activities in line with RRI (Responsible Research and Innovation) ethics.” He follows this up by saying they had to create two different data sets, which also meant adhering to GDPR very carefully. I felt pretty reassured after this explanation.

We are now heading into the last few minutes of our interview, so I really wonder what the future holds for the PARENT project. Jamal tells me that he expects the project to grow in the cities where it is active. Also, he predicts this large amount of energy consumption data could be extremely useful for energy regulators, energy grid operators, and other such actors. Jamal thinks “more research needs to be done about how this can be useful for urban electricity grid management.” I think back to the issue of scalability and ask, “is it ready to be scaled up to other cities all over Europe?”

Jamal explains that there is nothing theoretically stopping the PARENT platform being replicated in other cities. However, he does add that technology moves really quickly and that perhaps the PARENT platform should be opened up to other data monitors as this would allow the platform to have more flexibility in meeting demands. He also excitedly tells me about their exploitation plan: the platform is planning to improve its functionality. Jamal is ultimately hoping that the Platform can point us to our most energy intensive or energy inefficient devices. This would be great as I’m really suspicious about my fridge, but I can’t yet prove that it is making me poor, so a smoking gun would be great.

Jamal quickly reminds me, “when it comes to scalability the biggest question is where will you get the human resources to carry out the project?” Going into more depth, he says that different cities require different types of human interaction and this shouldn’t be underestimated. It’s clear that Jamal is very passionate about getting the message across about the need for a human touch, he says “we should not be reliant on the technology itself, in terms of community building. When you focus on a technology, you must always think about the human aspect of all of this.”

Finally, I ask Jamal for his most interesting conclusions about the project. He tells me that there is definitely scope for a lot of further research. I decide to press him for a more specific answer, he tells me, “we found a huge amount of activity going on, this activity all seems to share the same goals but don’t speak the same language.” In a few months, PARENT will share their thoughts in their final conference, to be held in Brussels. Jamal believes we need more coherent strategies to deal with this. Just so I don’t forget he reminds me one last time “technology cannot do this alone.”