Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

What is Co-location?

Cities can improve the efficiency of land use by increasing the number of similar activities (densification) or variety (intensification) in a given area. Co-location takes the form of either:

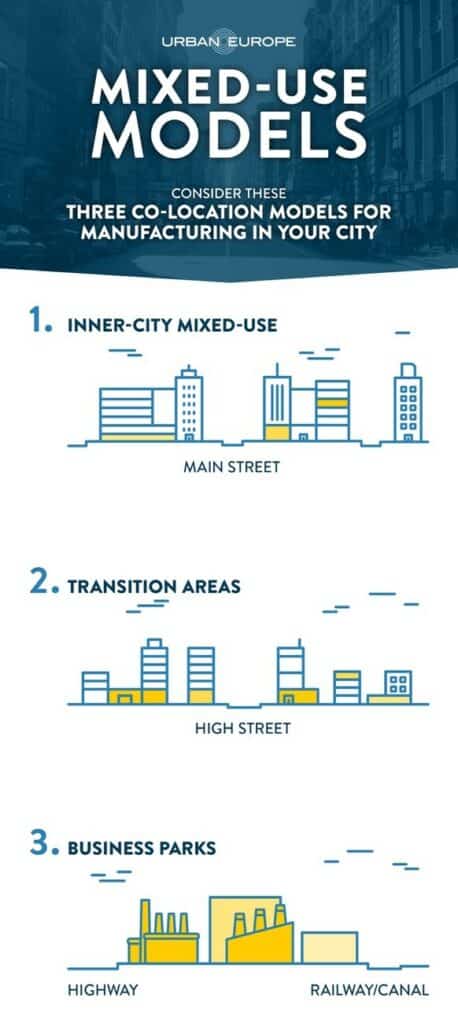

Co-location can manifest in the following three ways:

Inner-city mixed-use: mainly artisans and crafters who can work from small, dedicated spaces: homes, shared workshops. These may be temporary, situated above other makers, retailers, or residences, and can use space previously occupied by alternative uses.

Transition areas: medium-sized spaces set along high streets that house multiple businesses and functions of innovation, development, and production. Act as a ‘buffer’ to the heavier industry beyond.

Business parks: monofunctional land use. Least suited for mixed-use but effective for collating businesses that share a core product or process. Conflicts with residential due to risky or hazardous manufacturing, e.g., chemicals, fire and explosion risk, noise, dust, effluents, odours, waste, and wastewater.

Co-location was common in European cities until the 1960s when a lack of strategic planning set in, creating conflict between residents and functional land use. Although urban manufacturers often make the foundational goods which cities rely on, people-centred building regulations led to the ousting of manufacturing from urban centres. Production stagnated as land use became monofunctional: just residential.

The challenge now is to re-establish a diverse ecosystem of widescale production within cities and manage the tension between land use stakeholders.

Benefits of Mixed-Use Land and Co-location

Advantages of co-location for citizens and businesses alike are multi-faceted:

In sprawling cities, residents need to be mobile to access the desperate tapestry of functional modern life. Conversely, mix use zones mean it is theoretically possible within mere minutes to buy freshly baked bread, drop the kids off at nursery, walk to work, pop to the gym at lunchtime, and drink in the local bar in the evening. Convenient, vibrant living with minimum fuss, expense, time, congestion, and emissions.

Localisation economies, where businesses are clustered together, ease collaboration. Manufacturers that complement one another can share industrial commons, technology, equipment, services, personnel, skills, floor space, storage, and even transport. This avoids duplication costs and competition for specialisms in short supply. It provides chances to disseminate and hone a spectrum of practical and theoretical manufacturing skills, which creates a reliable intelligence base.

Co-location improves production chains and controls. Cities of Making found that high-end clothes designers in London like to oversee manufacturing, so favour proximity.

Being in close geographical confines makes competition visible, driving innovation and investment in research and training. It generates interdependence and a sense of community, breeding contractual and informal collaboration: a catalyst for new product and process development.

Challenges of (Not) Mixing Space

If there’s so much to gain, why isn’t co-location the default?

Housing shortages and chances to make more money per square metre from residential development pressures manufacturers to relocate. In Haringey, more than 60% of companies interviewed experience this. Those who relocate are typically pushed to the city peripheries, straining logistics, supply lines, and links to clients. Those who remain face rent hikes in line with residential and commercial properties, limiting capital and their ability to invest and compete.

Makers come in many shapes and sizes – from micro-manufacturers to huge producers. Their spatial needs vary but include room for workers, (large, immovable) equipment, storage, vehicles, and materials. Most cities do not offer the diversity of suitable spaces to match, defaulting to standardised sizes and rents, which limits the potential for entrepreneurs to establish side lines and grow their businesses. In Brussels, unsuitable and poor quality properties forced companies to ‘make do’ with rooms requiring “major works to bring them up to standard”. This is costly.

Some manufacturing isn’t suited to co-location because of by-products that don’t mix well with other land use: fumes, odours, noise, vehicle movement, congestion, fire hazards, child safety risk, or even explosions and dangerous chemicals. All forms of making tend to get labelled with these issues. It’s what keeps the important “basic metabolic work” of Brussels’ wastewater processing and building material recycling on the outskirts.

At the other end of the industrial scale, craftspeople and ‘hobby makers’ can work from home, selling directly using online marketplace platforms, but draw ire for using machinery during antisocial hours.

Attempts to introduce mixed spaces by design are almost always at the hands of housing developers. Limited experience with industrial space and interpreting co-location policy means they “risk making irreversible errors” by overlooking access needs, noise autarky, and flexibility.

Findings from OPDC indicate it’s best not to over-densify. Where mixing occurs, even unfounded nuisances – such as steam mistaken for noxious gas – create tension with neighbours. Residents are effective in grouping to voice their complaints. They are favoured by public authorities, even if manufacturing is in the majority in floor area terms. As a result, producers are often forced to adapt their practices.

Solutions: How to Create Co-location

Without intervention, co-location struggles to take hold. Authorities, planners, developers, and policymakers should consider the value of introducing diversification policy and properties that successfully underpin a breadth of urban manufacturing.

Industrial builds are generally cheap constructions and poorly insulated. Investing in acoustic attenuation and filtration quietens activities, retains dust, and contains emissions, making manufacturing more compatible with housing and retail. Double up with detached rather than conjoined units.

Design in storage areas, especially for companies selling directly to customers. Sharing courtyard spaces provides much-needed storage for small-scale manufacturers and hides blight from public areas.

Devise a structure plan to “guide the distribution of mixed-use areas” at a city-wide scale to provide a choice of working spaces and to mitigate problematic piecemeal development. Factor in public and private transit links for access by employee and resource bases.

Businesses should be represented in planning. A city Curator is ideally positioned to broker a better relationship between actors and a dialogue that leads to understanding disparate needs and finally a shared solution or compromise.

Contain nuisances to improve public relations by:

Developing a range of unit sizes, shared rooms, and affordable rents, rather than standardised spaces and charges. This caters for variable sizes of manufacturers, attracts a diverse mix of makers, and enables them to scale up and down.

Reuse basements and former offices, empty shops along high streets, and reinforced multilevel structures like car parks.

Blend in out-of-work-hours activities such as concert venues, gyms, libraries, community centres or maker spaces to soften the confronting presence of production on the doorstep.

Densification safeguards a company’s position in the city by making it harder for housing to force out business. Vertical making increases the concentration of manufacturing within minimum ground area. Execute it well, and multiple makers can co-exist with residential or retail within a single block without conflict. Raising production skywards is effective at mitigating noise heard below.

Proximity to resource supply and demand from clients means vertical manufacturing circumvents inflating costs associated with horizontal sprawl and transportation:

Small-scale makers, repair shops, and artisans can repurpose rooms above shops and factories, utilising vacant lots. Design in goods lifts, large openings, and load-bearing floors to make access and storage of even large, heavy goods possible at height.

Traditional manufacturers need central protections to save them from losing out to high-tech businesses.

Authorities in Cureghem, an area of Brussels, stimulated manufacturing by supporting newer businesses with reduced rents, recruitment services, and assisted integration into residential developments.

City authorities could offer:

Mixing tenure models allows makers to prosper. It grants access to suitable spaces and enables diverse business types to co-exist and collaborate, acting as an incubator – a concentration of similar business types – that leads to innovative product developments, stronger competition, and a resilient city economy.

In a Nutshell

Cities have much to gain by fostering sharing spaces at a building, block, and neighbourhood scale. Consolidating problematic manufacturing in microzones or city peripheries improves the public image of cleaner inner-city makers, paving the way for them to exploit opportunities of working from homes, shared areas, high-rises, and vacant spaces. Co-location creates a sense of community and interdependence. It is a vital tool for product innovation, sharing knowledge and equipment, cost-cutting, and access to labour. If decision-makers and planners act appropriately to safeguard urban manufacturing against the external pressures from real estate development, it can once again become a stable feature of our cityscape.