Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

BRIGHT FUTURE Blogs. Corby: past, present and future of the (post-)industrial city

In our JPI Urban Europe project ‘Bright Future for Black Towns’, we want to develop place-specific strategies for small and medium-sized European industrial towns. Our case study towns have all had an economy dominated by manufacturing and/or mining industries throughout most of the 20th century, or sometimes even already longer ago. Some towns lost their industries and struggle to find alternative economic perspectives; others managed to modernize their industries or attract ew industries instead. Our case study towns are Velenje (Slovenia), Fieni (Romania), Kajaani (Finland), Heerlen (Netherlands), and Corby (UK).

Though Corby’s history goes back many centuries, most of present-day Corby was built after World War II. The main forces behind its fast economic growth since the late 19th century were first iron ore extraction and later the steelworks and tube works. The tube works became famous for building the PLUTO undersea oil pipeline to provide fuel to the Allied forces after the D-Day invasion. Another significant growth incentive was Corby’s designation as one of England’s New Towns in 1950. Corby transformed from a rural village of about 1500 inhabitants in 1931 (much of the old village can still be found at the city’s eastern edge) to a medium-sized city of about 53,000 inhabitants in 1981. In 1980, the British Steel steelworks was closed, causing 11,000 people to lose their jobs within 2 years. The tube works remained though, and Corby’s city government and citizens managed to convince the UK and EU to support urban and economic regeneration programmes. Since the 1980s, Corby has managed to diversify its economy, though manufacturing is still one of the dominant economic sectors.

Photo credit: Marco Bontje

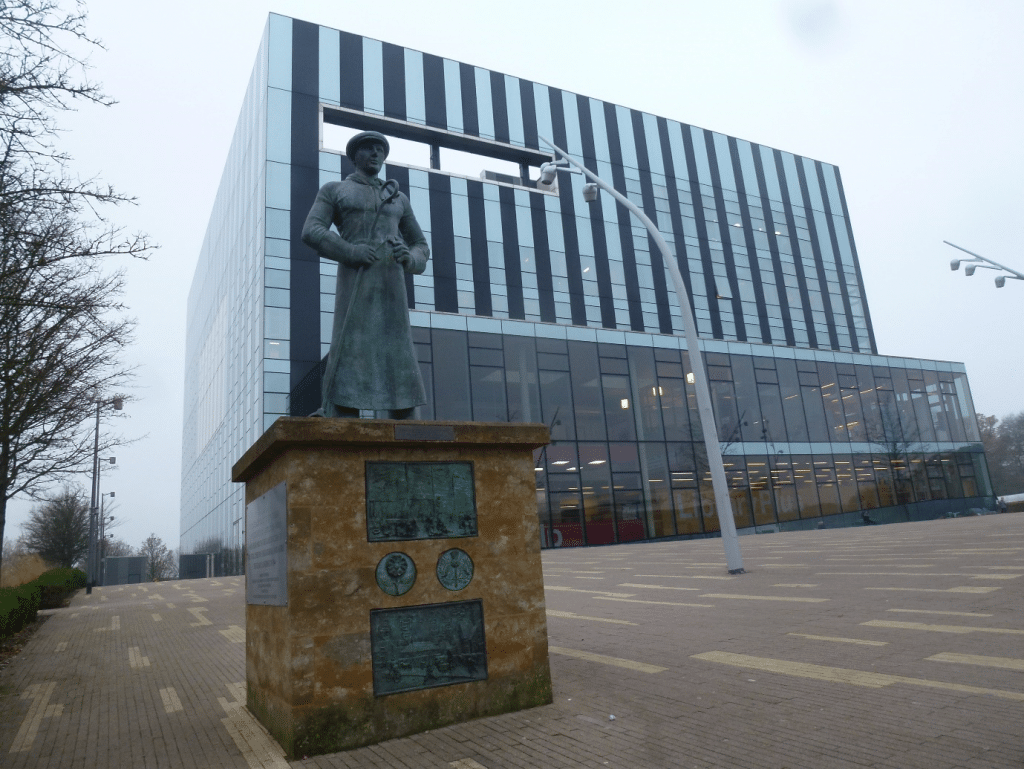

In recent years, at first sight, Corby seems to be doing remarkably well again. After some decades of population stagnation, it became one of the fastest-growing municipalities of England after 2001; meanwhile Corby has about 67,000 inhabitants. Moreover, after tough economic times with high rates of unemployment and welfare dependency in the 1980s and 1990s, meanwhile Corby’s unemployment is even below the UK average. The local government developed ambitious plans for further growth and invested in better rail connections to London and upgrading the town centre. The Cube, opened in 2010, is the clearest example of these upgrading ambitions. It houses local council services, a library, a theatre, and workshop spaces.

Corby’s population has shown an admirable resilience in tough times and may now be heading for a brighter future. Still, as becomes clear from the analysis of our UK project colleagues, Corby’s economic, societal and urban development is vulnerable in many ways, and there are still enough challenges to face. In earlier stages of our research project, we explored the dominant narratives and alternative narratives of our towns’ past, present and expected future. In Corby, it appeared that each dominant narrative has at least one equally powerful alternative narrative as its counterpart. In interviews and workshops with residents, policy-makers and other local stakeholders, Corby’s dominant narratives could be summarized as follows. Until the early 1980s, the steelworks dominated Corby’s economy, but also changed its population, culture and identity. The closure of the steelworks caused a severe crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, in which some even described Corby as a ‘ghost town’. However, in the early 21st century the dominant narrative became ‘phoenix town’, a town rising and leaving industrial decline behind. Alternative narratives, though, nuance or doubt each of these three phases of the dominant narrative. The steelworks were also dangerous and polluting, and there were also other important industries. After the steelworks closed, people were not only leaving town, but many were also staying in or even moving to Corby, and those staying mobilized for the town’s future and supported each other through difficult times. The recent ‘phoenix’ narrative may also be exaggerated, and it is definitely not growth and recovery for everyone. Some interview respondents were worried that recent growth of population and housing and the local government’s plans for further expansion are outpacing infrastructure and service provision, possibly leading to an unbalanced development. Another development resulting in mixed emotions is the recent increase of international migration to Corby. Corby has a strong tradition as a migrant destination. The steelworks and tube works attracted many workers from Scotland, still many residents have Scottish roots, and Scottish culture is prominently present in town. The more recent labour migrants from Central and Eastern Europe, though contributing significantly to Corby’s economic recovery, may not feel equally welcome. Despite its high share of first- and second generation migrants and its export-oriented industries, Corby had one of the highest pro-Brexit growth rates in 2016. During our visit, we noticed that Brexit support was still clearly expressed in town; for example in our hotel, but that was probably rather because of the hotel / pub chain owner’s personal political preferences.

Photo credit: Marco Bontje

At our project meeting in November, we discussed the project’s next phase: an assessment of our towns’ social sustainability and a series of workshops to explore possible social innovations. Art and cultural projects could be important elements of such social innovations. Such projects can reach parts of the population not actively involved in the development of their town before, lower the threshold of art and culture to a broader audience, and contribute to strengthening local identity and pride. Our UK partners, together with their local contacts, could show us some inspiring examples of recently completed, on-going and soon to be expected projects in and around Corby.

One of these examples is the Rooftop Arts Centre where part of our meeting took place. Here we discussed several initiatives to promote art, culture and creativity, in a town where cultural facilities as well as interest in and active participation in culture are (or were) rather scarce. The Rooftop Arts Centre offers workspaces to artists and actively involves local artists as well as inhabitants in exhibitions, workshops and events. It is temporarily located at the top floor of a shopping centre. After meeting with some of the key persons of Corby’s cultural scene here, we created our own piece of art: a photo collage of the five case study towns of our Bright Future project.

Photo credit: David Bole

Another inspiring example discussed during our meeting, or actually a programme full of inspiring examples, is Made in Corby. This programme started in 2013 as part of the Creative People and Places Network of Arts Council England. Meanwhile Made in Corby has already organized about 800 events and activities. The main aim is to involve more people in art experiences. Next to many smaller meetings and events, some of the most remarkable achievements were the Grow Festival, the Big Ideas programme, the musical Danny Hero, and the book and exhibition Living Legends: Hidden Histories. For Living Legends, Corby’s inhabitants were asked to nominate people with extraordinary stories, achievements or experiences. Ten nominees were selected to tell their story in the book and the exhibition. It is a great example of an initiative relatively small and easy to organize, but having a big impact on a community.

Though such initiatives are indeed inspiring, also for other smaller industrial towns, the future perspective for art and culture in Corby is still uncertain. Made in Corby is a temporary programme. It will certainly be funded until 2020, but what happens afterwards? Similarly, what will happen with the Rooftop Arts Centre after it may have to leave its current temporary location? And will the Cube really manage to keep attracting residents to cultural events, including those that would normally not go to theatres? Though many Corby residents will probably know how to find the theatre, it seemed a bit ‘hidden’ within the Cube. The workshop facilities we used for our meeting, in a basement without daylight, also did not look very inviting. There is definitely still room for improvement for art and culture in Corby. Art and culture deserve to be more prominently present in town.