Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

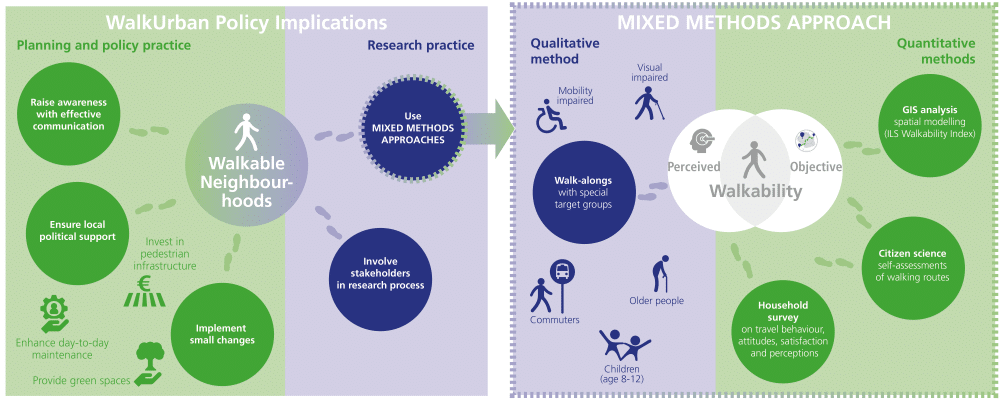

Working across three European cities – Gothenburg, Dortmund, and Genoa – this project’s researchers developed new tools and methods for understanding what makes cities truly walkable. Their study of six neighbourhoods, examining both middle and lower socioeconomic areas, revealed important insights about how different groups experience and use pedestrian spaces.

A New Way to Measure Walkability

One of the project’s key achievements was developing the Short Perceived Walkability Scale, a framework that examines five critical aspects of the walking experience. At the foundation lies feasibility – essential elements like pavement condition and adequate pavement width. Building up through convenience and comfort, the scale extends to whether walks feel pleasant and ultimately stimulating.

Testing this framework across 1,103 households revealed crucial insights. “People who perceive better walkability walk more in both duration and distance,” Noriko notes. The research also showed cities must get the basics right before aiming higher. Specific information about walking routes was also collected. In Genoa, for instance, about 50 respondents took part. While they appreciated the stimulating aspects of their walks, poor pavement conditions created significant barriers. The study found that almost half of the respondents in Genoa 47% of respondents strongly disagreed with the statement “the pavement is in good condition.” Noriko explains, “If the street is very dirty or there is rubbish on the ground, people don’t want to walk even if there is nice street furniture.”

Beyond Numbers: Understanding People from All Walks of Life

Another key project outcome was pioneering a comprehensive approach to understanding different pedestrians’ needs. While household surveys provided broad insights, walk-along sessions with children, older people, and those with disabilities revealed perspectives that might otherwise have been missed.

In Genoa, researchers worked with schoolchildren participating in the “pedibus” (walking bus) program. “Children told us they liked nature – trees, animals, birds, and flowers,” Noriko shares. “But they were very concerned about safety, such as traffic crossing quality and traffic speed.” This approach proved particularly impactful in Sweden, where social media posts about the children’s walk-alongs in Gothenburg received over 200,000 reactions.

The walk-alongs also revealed how traditional surveys might miss key user groups. “Most able and young can participate in household surveys,” Noriko notes, “but children can’t participate in household surveys, and disabled or older people often have problems with online surveys.”

The Power of Municipal Partnership

One of the project’s most striking findings concerned the value of municipal involvement. In Genoa, having the municipality as a direct partner significantly enhanced its impact. The city connected WalkUrban’s research with existing initiatives like their pedibus program and tactical urbanism experiments, creating what Noriko calls “a win-win situation.”

The Genoa team achieved its success by engaging mobility managers in local companies. They also shared experiences with other Italian municipalities, including Turin, Milan, and Bologna, extending the project’s impact beyond its original scope.

Small Changes can Lead to Big Impacts

The project’s research revealed that significant improvements don’t always require major infrastructure projects. In examining both objective and perceived walkability, researchers found that basic maintenance and small interventions could make substantial differences.

“Rather than changing the entire street, we can improve what’s there,” Noriko explains. The project identified opportunities for small-scale interventions like adding planters or improving street cleaning – changes that could significantly improve perceived walkability without requiring major investment. However, the project’s researchers also noted that going beyond simple infrastructure changes is also essential to consider. For instance, improperly parked cars were an issue in Genoa and Dortmund, whereas in Gothenburg there was much more respect for the rights of pedestrians.

Cultural Differences and Common Ground

Studying three distinct European contexts revealed both unique challenges and universal needs. The project’s GIS analysis examined objective walkability factors like proximity to amenities and green space coverage. The Swedish city Gothenburg scored highest on these objective measures, with its extensive pedestrian infrastructure and public transport-oriented town centres.

Despite challenging weather, Gothenburg had a score of 4.0 out of 5.0 on the Short Perceived Walkability Scale. The Swedish team’s success extended beyond the project itself, as they effectively shared findings with other Swedish municipalities.

On the other hand, Genoa faced different challenges with its hilly topography requiring numerous stairs and slopes. Despite these infrastructural issues and scoring lowest on perceived walkability (3.5), the city showed how engaged municipal leadership could drive positive change. Their success stemmed partly from collaborating with other projects, including EXTRA’s tactical urbanism initiatives and JUSTICE’s work on accessibility needs of disadvantaged people.

Bridging Research and Policy

Perhaps most importantly, the project demonstrated the value of combining different research methods. Their mixed-method approach, using everything from GIS analysis to children’s walk-alongs, provided a more complete picture of walkability than any single method could achieve.

The research also revealed important lessons about implementing change. The German experience showed that policymakers need both problem identification and positive examples. “When we talk to politicians,” Noriko reflects, “we need to tell them not only bad things but also positive things.”

Creating Lasting Change

Walk Urban’s findings are already influencing policy. The project’s tools, particularly the Short Perceived Walkability Scale, give cities practical ways to assess and improve their walking environments. Their booklet, aimed at decision-makers and the wider public, is available in four languages and provides municipalities with clear guidance for creating more walkable neighbourhoods.

Most significantly, their research shows that while walking might be free, creating truly walkable cities requires systematic investment in both infrastructure and engagement. As one Swedish partner noted, implementing these policy findings will take time, but the project has created a clear pathway for cities seeking to put pedestrians first.