Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

When Data Meets Daily Struggles

The project’s most significant innovation came from connecting quantitative approaches with qualitative ones. Justice’s researchers extended the capabilities of Open Trip Planner, an open-source tool for measuring transport accessibility, to account for diverse user needs. While public transport accessibility researchers have long used this tool, the JUSTICE project broke new ground by adapting it to consider the needs of multiple vulnerable groups simultaneously.

Through “go-alongs” – accompanying vulnerable users on their journeys – researchers uncovered crucial insights that pure data missed. “We discovered people often avoid certain stations that our models considered optimal,” explains the project’s coordinator, Alexis Conesa. “They would take longer routes to avoid complex transfer points that, while technically efficient, proved challenging to navigate.”

These observations revealed how standard accessibility measures fall short. At Strasbourg’s main transit hub, for example, researchers found that visually impaired users deliberately chose longer routes to avoid transferring there despite its central location. The convergence of multiple tram lines and busy spaces created an environment that, while efficient on paper, proved overwhelming in practice.

The go-alongs also revealed subtle barriers that wouldn’t show up in traditional analysis. Some users, despite having legal rights to priority seating, felt too shy to claim these seats. Others struggled with complex stations where multiple transport modes converged, preferring simpler but longer routes. These insights led researchers to develop the concept of “complex stations” – transit points that vulnerable users systematically avoid despite their theoretical efficiency.

Making Invisible Barriers Visible

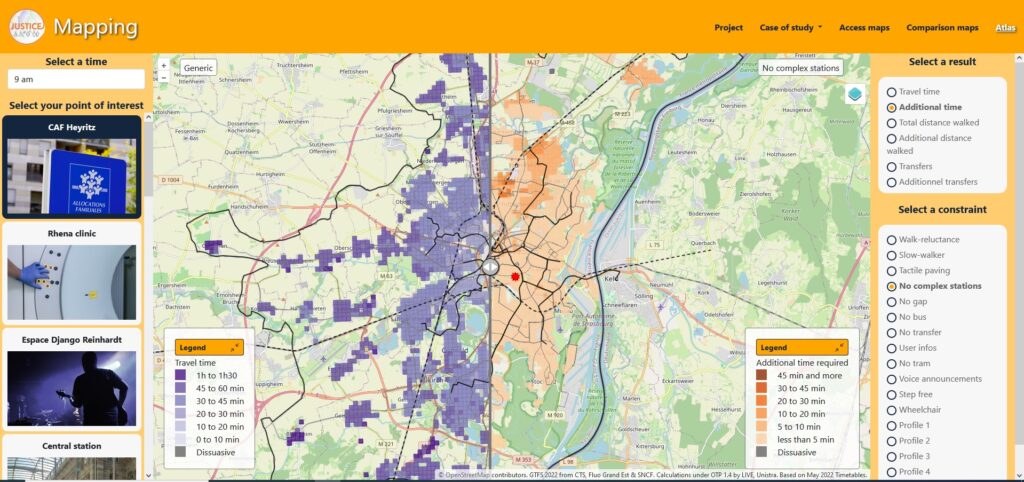

In Strasbourg, the project developed an innovative mapping platform called Atlas that innovates how transport planners visualise and address accessibility gaps. The interactive tool helps identify systematic infrastructure gaps, such as missing tactile paving for blind users. “The platform shows exactly where improvements are needed,” Alexis notes, “allowing municipalities to plan systematic upgrades along entire routes rather than piecemeal fixes.”

The tool’s power lies in its ability to show the impacts of current accessibility barriers on various user groups and for different schedules. Conversely, simulating scenarios of accessibility upgrading in the input data would allow transport planners to see how changes might affect different types of users, incorporating insights gained from the qualitative research.

In Brussels, where decades of transport development created a complex network of metro, tram, and bus services, researchers developed scenarios to help evaluate different improvement strategies. The city faces unique challenges with its mix of historic and modern infrastructure, underground stations, and multiple transfer points. Transport planners used these simulations to evaluate various scenarios: Should they prioritise major hubs? Focus on specific lines? Or implement citywide accessibility improvements? The quantitative analysis in Brussels helped decision-makers understand how each approach would impact different user groups.

From Research to Reality

The project’s impact extended beyond research into concrete improvements. In Konya, Turkey, exposure to solutions from other cities accelerated the implementation of accessibility kiosks at key stations. These devices enable vulnerable users to alert bus drivers about their needs in advance, ensuring appropriate assistance with boarding and alighting.

While Konya had conceived the kiosk concept before the project, JUSTICE helped refine its implementation through extensive stakeholder engagement. Working with local disability associations, the team determined optimal kiosk locations and features. This collaborative approach ensured that the solution met real needs rather than just theoretical requirements.

The project also fostered valuable knowledge exchange between cities. Visits to Brussels and Strasbourg helped Konya’s planners understand different approaches to accessibility, while their experience with the kiosk system provided insights for other cities considering similar solutions.

Giving Voice to the Voiceless

The JUSTICE project placed procedural justice at its core – ensuring vulnerable users have a meaningful voice in decisions affecting them. Through carefully structured workshops, the project brought together policymakers, experts, and user representatives to discuss priorities and trade-offs.

“These discussions created crucial dialogues,” Alexis explains. “Policymakers could explain budget constraints, while users could demonstrate why certain improvements were essential. It created a space where vulnerable people were truly heard.”

The project’s final event in Strasbourg exemplified this approach, bringing together international experts, local politicians, and user representatives. Featuring prominent accessibility researchers like Karen Lucas (The University of Manchester) and Karel Martens (Technion – Israel Institute of Technology), along with local decision-makers, the event demonstrated how academic insights could inform practical policymaking.

To reach broader audiences, the project even produced a YouTube video documenting the challenges faced by visually impaired users in Strasbourg. This visual storytelling helped communicate complex accessibility issues to both decision-makers and the general public.

Also, in terms of communication, the project’s approach to stakeholder engagement, combining formal workshops with hands-on observations, provides a template for cities seeking to understand and address accessibility challenges. The project showed that meaningful improvement requires both technical innovation and genuine user engagement.

Creating Truly Inclusive Transport Systems

The JUSTICE project demonstrates that improving transport accessibility requires complex data and human insight. As noted above, it reveals how supposedly “optimal” routes can fail vulnerable users and challenges cities to think differently about transport planning.

The project’s emphasis on procedural justice – ensuring vulnerable users have a voice in decisions affecting them – provides a model for truly inclusive transport planning. As cities worldwide grapple with making their transport systems more accessible, the JUSTICE project offers both practical tools and a proven methodology for bringing about meaningful change. It shows that true accessibility isn’t just about infrastructure – it’s about understanding and responding to the real needs of all kinds of users.