Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

Agroecological farming practices can be defined as those that centre both the ecological context and social justice concerns, and recognise the interconnection between people’s health, plant health and soil care. Chiara explains these considerations are what separate agroecological farming practices from other types of agriculture, and even more so from urban agriculture. She says, “urban agriculture can be totally soilless, growing into a building using artificial chemicals, it can be energy intensive, without any concern for soil or who grows it.” Michiel underscores that in reality 70 percent of the world’s food supply is produced agroecologically, which means food is grown ecologically by smallholder farmers, as opposed to using industrial farming practices, and it is actually urban areas that maintain our unsustainable farming practices.

One of the key project findings is that at present there is little connection between much of the movement for sustainable food planning within cities and the agroecological farming movement, such as La Via Campesina. Most sustainable food planning initiatives are conceived within academic and policy contexts and overfocussed on the consumption side of the urban food question. When they do think about food production, they tend to look at ways to retrofit food in cities. Significant attention is placed on high-tech urban agricultural solutions without questioning the existing dynamics of urbanisation that consume urban soilscapes and peri-urban farmland, showing little understanding of soil biology and its importance to produce healthy and nutritive plants. Whereas the agroecological farming movement emerged from concerns for the ecological impact of the agro-industry, so much of its work has been pioneered by farmers and indigenous communities for generations. The project’s analysis shows the disconnection between the sustainable food planning and the agroecological movements stems from their differing origins. Another issue that presents urban decision makers with a problem is that there are very few cities they can examine that have explicitly adopted agroecological practices.

Yet, the project does identify the city of Rosario in Argentina as a positive example of how urban agroecological farming practices can achieve sustainable outcomes by centring smallholder farmers. Rosario managed to take derelict land with poor soils and regenerate them into productive urban farming spaces. Not only have the city’s urban farms increased soil health, but they have also reduced flood risks by providing spaces for water absorption. Additionally, these farms reduce the number of urban heat islands in Rosario, since the green spaces absorb excess heat. Rosario has been so successful in the development and implementation of agroecological farming as a public policy that it won the World Resources Institute’s Grand Prize for 2020-2021 for its sustainable food production programme.

The origin of this success can be traced to an urban agricultural programme initiated in 2002 which evolved into a comprehensive “agroecology as public policy” approach. That programme used agroecological knowledge to develop a jobs creation programme centred on an influx of smallholder farmers coming into the city. These farmers were made landless by a combination of the Argentinian economic crisis of 2001-2002, and the more long term conversion of the surrounding province’s (La Pampa) arable land area into large-scale industrial transgenic soy farms focused on exports. The programme leveraged the farmers’ expertise in soil care to turn unproductive urban land into productive urban agricultural spaces. The project’s partners in Rosario say Urbanising in place’s work has promoted the design of Rosario’s agrarian park, whilst also supporting its producers by providing sustainable equipment, such as a solar air heater, solar driers, an ecological toilet, and a greenhouse for vegetables. Today, Rosario shows a comprehensive set of policies that range from banning non-agroecological farming within a certain buffer of the city, to coaching for agroecological transitions, to market access, a municipal seed bank, access to urban organic wastes and other important farming infrastructures.

Urbanising in place’s work has promoted the design of Rosario’s agrarian park, whilst also supporting its producers by providing sustainable equipment, such as a solar air heater, solar driers, an ecological toilet, and a greenhouse for vegetables

A key policy lesson coming out of the project’s analysis is that even with broad policy frameworks, municipal planners need more knowledge on agroecological practices to make them viable. An example can be found from the project’s work in London. A key project partner in London, Quantum Waste, aimed to pilot an urban farm initiative that would use restaurant food waste to remediate urban soil. The plan was very much aligned with the European Green Deal, and the Farm to Folk Strategy’s vision for the management of urban organic wastes. Yet, the municipal planning department rejected their proposal, declining to recognise Quantum Waste’s composting work as relevant to farming. They also rejected their request for a living permit for their farmland in the greenbelt, making the project unviable for smallholder farmers. Quantum’s case was demonstrative of the lack of agroecological knowledge that is typically found at the municipal level.

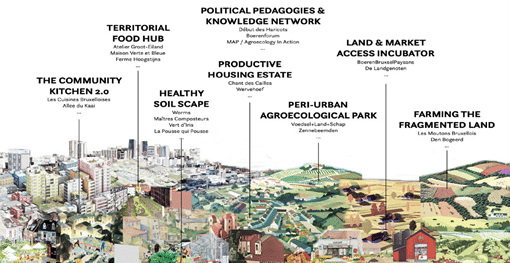

In order to address the knowledge gap on agroecological practices, the project has identified eight building blocks offering the direction necessary for implementing an agroecological urbanism. These building blocks (as seen below) will be connected to a modular online resource, demonstrating the practical application of each block to one of the project’s cities (London, U.K.; Riga, Latvia; Brussels, Belgium; and Rosario, Argentina). Michiel emphasises that the project’s contribution is not just identifying that “organic waste improves soil,” but rather establishing the missing links that policy makers need to understand if they want to create an agroecological urbanism. This resource will highlight the kinds of infrastructure, knowledge, institutional capacity, and the types of risk sharing that are necessary for success.

Mapping of the Brussels context in light of the Building Blocks

Reflecting on the long-term impacts of the project, Michiel and Chiara identify three important outcomes. Firstly, several cities have been brought into constructive and educational conversations. For instance, uniquely, the general populace of Riga already has widespread access to land and knowledge on foraging and growing. Yet, only through the communication between the four cities has Riga’s exceptionality been highlighted to its own decision makers. Secondly, the Brussels Capital Region has understood if it is to meet its goal of producing 30% of its food locally by 2035, it must build capacity for agroecology. So, a commitment has been made to develop a centre for urban agroecology. An ex-farmer (Jan Pille) has already been appointed to explore the practicalities of development, and a call has been made to make the Zavelenberg (a centrally located space zoned for agriculture) available to agroecological farmers. Lastly, Urbanising in Place has contributed to the development of two important follow-up projects: in the UK, a coalition of key players lobbying policy makers to promote agroecological fringe farming within several large cities , and internationally, the SOIL NEXUS project, which will design policy tools for using water and waste for urban soil remediation.

“We have to look at farmers not as communities of people on the way out, but as communities of people on the way in”

Summing up the conversation, Michiel and Chiara agree this project shows there is a need for agroecological infrastructure, reterritorializing space for farming, introducing principles of care which centre of people and soil care, and to address the politics of knowledge (how knowledge or a lack of knowledge impacts policy). Michiel finishes by saying that in an ever-urbanising world farmers, particularly smallholder farmers, are seen as a thing of the past. However, if our sustainability targets are to be achieved, particularly in urban areas, “we have to look at farmers not as communities of people on the way out, but as communities of people on the way in.”