Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

Water scarcity is one of the key policy challenges of the 21st century. According to one assessment, by 2050 the percentage of the global population facing water scarcity will have risen from 33% to 50%, and other research shows that four billion people are already living under conditions of severe water scarcity for at least one month every year. Making matters worse, climate change and urbanisation are exacerbating existing global water insecurity. This is an especially troubling fact for countries like Jordan and India because both of these countries are already experiencing water scarcity issues and are expecting increasing urbanisation and population levels. The FUSE project offers planners in both of these countries water-focused models that project long-term water supply and demand. These policy-evaluation models assess the efficacy of a range of water security interventions under future climate, demographic, and land-use changes. The project’s coordinator, Professor Steven Gorelick, tells us in more detail about the project’s achievements in Jordan and India.

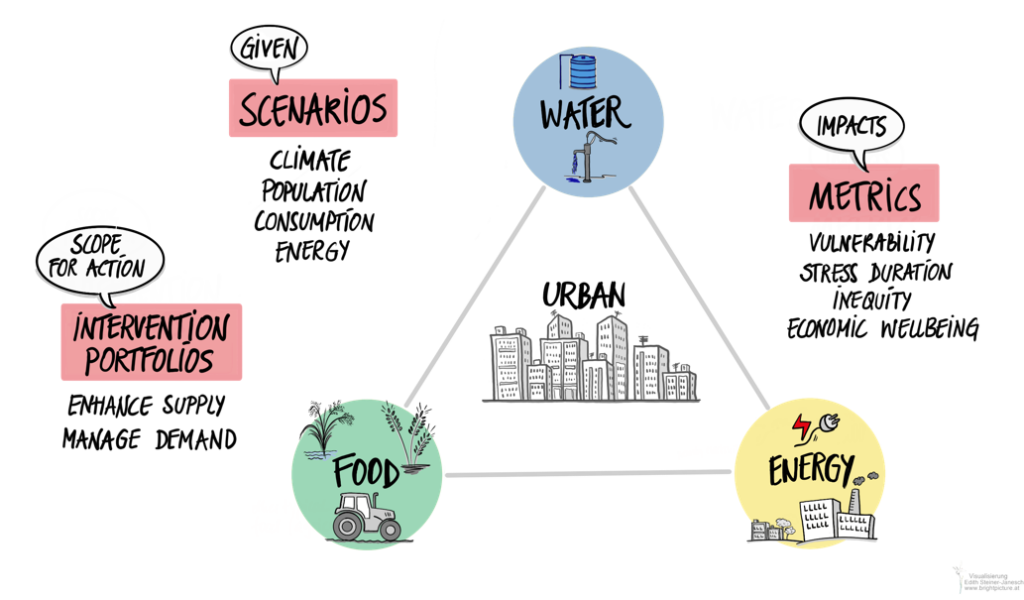

The key project outcome in Jordan was the creation of the Jordan Water Model (JWM). The JWM is arguably the most detailed and comprehensive national water model anywhere on Earth. The need for such a detailed model can be understood by putting Jordan’s water scarcity into context. The UN Food and Agricultural Organization classifies absolute water scarcity as a national water allocation level of less than 500 m3 per capita per year; in Jordan, per capita water availability is just 135 m3. This is why the project’s goal was to produce a credible model that can effectively serve as a policy-evaluation tool of value to water managers. To achieve this, a nexus approach was taken, which accounts for the interrelations among food, water and energy systems. Steven explains that, for example, within their nexus model, farmers’ water-use behaviour is treated realistically, understanding farmers act to maximise profits but also elect to plant crops that they have grown historically, even if this reduces profits.

farmers’ water-use behaviour is treated realistically, understanding farmers act to maximise profits but also elect to plant crops that they have grown historically, even if this reduces profits.

Water allocation projections for four plausible scenarios

The JWM has already received serious attention from Jordan’s water planners for its ability to produce detailed projections and because the model was developed in consultation with local experts at the Jordanian Ministry of Water and Irrigation. The JWM offers planners water allocation projections for four plausible scenarios: an optimistic one with moderate climate change; one centred on drier climate conditions, one on population growth, and a crisis scenario in which Jordan sees severe climate change, a future refugee wave, population growth, crop price increases, and reduced transboundary river flows from Syria. For each scenario, the JWM gives planners estimates of monthly per capita water allocation until the year 2100. The model distinguishes the expected water allocation for the poorest 10% of Jordanians from the rest of the population, it also shows planners the expected disparity in per capita water usage, and the expected duration of water shortages for each demographic group in Jordan. Using these metrics, water planners have been given important information for assessing water security intervention options.

A plausible crisis scenario in which Jordan sees severe climate change, a future refugee wave, population growth, crop price increases, and reduced transboundary river flows from Syria.

The JWM was used to assess the efficacy of a number of water security interventions under each scenario. The results clearly show that Jordan has no choice but to pursue the most comprehensive plan for increasing water security. Steven says that even in the most optimistic climate change scenario, a business-as-usual approach would lead to 45% of Jordan’s population receiving less than 40 litres of water per capita per day. However, applying a strategy that transfers 25% of the groundwater used in agriculture to urban areas, combined with enhancing water supply by obtaining desalinated water from the Red Sea, and managing demand by implementing water saving measures would substantially reduce water insecurity under every scenario, except the worst case one. However, for all scenarios, pursuing such aggressive action keeps household water vulnerability by 2100 below 33% for both higher and lower-income households.

A model that treats Pune’s food, water and energy system as a holistic nexus

In India, FUSE has successfully produced a conceptual model and a preliminary integrated model for the city of Pune and the Bhima basin, identifying 22 key challenges for its food, water and energy systems. The model treats Pune’s food, water and energy systems as a single holistic food-water-energy (FWE) nexus. This nexus approach is reflected in the conceptual model itself, showing how one system connects with another. For example, it visually demonstrates that the environmental impacts of the energy system influence land use change for food production. The model also distinguishes between exogenous pressures, such as population growth, which decision-makers do not have control over, from endogenous ones, such as agricultural groundwater over-abstraction, where decision-makers may have regulatory authority to create a direct intervention. The conceptual model has aided the project by identifying where efforts should be concentrated as model development continues.

The model distinguishes between exogenous pressures, such as population growth, which decision-makers do not have control over, from endogenous ones, such as agricultural groundwater over-abstraction, where decision-makers may have regulatory authority to create a direct intervention.

In its stakeholder workshops, facilitated by FUSE team member the Austrian Foundation for Development Research (OEFSE), Pune’s cooperative culture was identified as a key strength for tackling these FWE challenges. The project encountered extremely strong interest from various stakeholder groups, which Steven attributes to India having a more bottom-up societal structure compared to many other countries. In their experts’ workshop, they successfully identified potential interventions the city could implement to tackle the impacts of rising temperatures, extreme rainfall events, urbanisation, land transformation in the peri-urban rural areas, and increasing electricity demand and insecurity. Some of these interventions are being assessed using a recently built model which employs the same framework that created the JWM. However, the Pune model had to be built from the ground up as monsoonal hydrological conditions, in particular, are significantly different in India when compared to Jordan. Here, FUSE’s researchers had to consider interventions and strategies that also address periods of greater flood risk along with those causing water scarcity. Over the next two years, the team aims to complete the Pune policy-evaluation model and explore a similar range of policies for India’s water planners, analogous to what they provided to Jordan’s water planners.

Steven concludes the discussion by focusing on the idea of credibility. The team’s work in Jordan was a success because of its attention to rigour and the needs of water planners. The team is hoping to replicate this success in India. Steven is careful to emphasise that there are a lot of nexus-system models out there, but most of them are “toy models” and of limited practical use to planners. This is not the case with the JWM and the ongoing Pune model’s development. Steven thinks FUSE’s strong mix of social scientists, natural scientists, and expert workshop facilitators was a key element of the project’s success. In his opinion, increasing funding timeframes for these kinds of projects and allocating a budget to local partners are measures likely to increase the adoption of policy-evaluation models as practical tools. For now, FUSE has shown that its framework for modelling can be applied anywhere as long as diligent attention is given to local biophysical and socioeconomic factors in a co-creation process with local experts and stakeholders.

FUSE’s strong mix of social scientists, natural scientists, and expert workshop facilitators was a key element of the project’s success.