Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

“Today, trains work according to a timetable, and when something happens, an operator decides how to deal with traffic, so delays don’t propagate through the network,” explains Paola Pellegrini, the project’s coordinator. She adds, “but with networks becoming increasingly complex, we wanted to explore if trains could have their own ‘brain’ and negotiate with each other.”

Shifting Away from Central Control

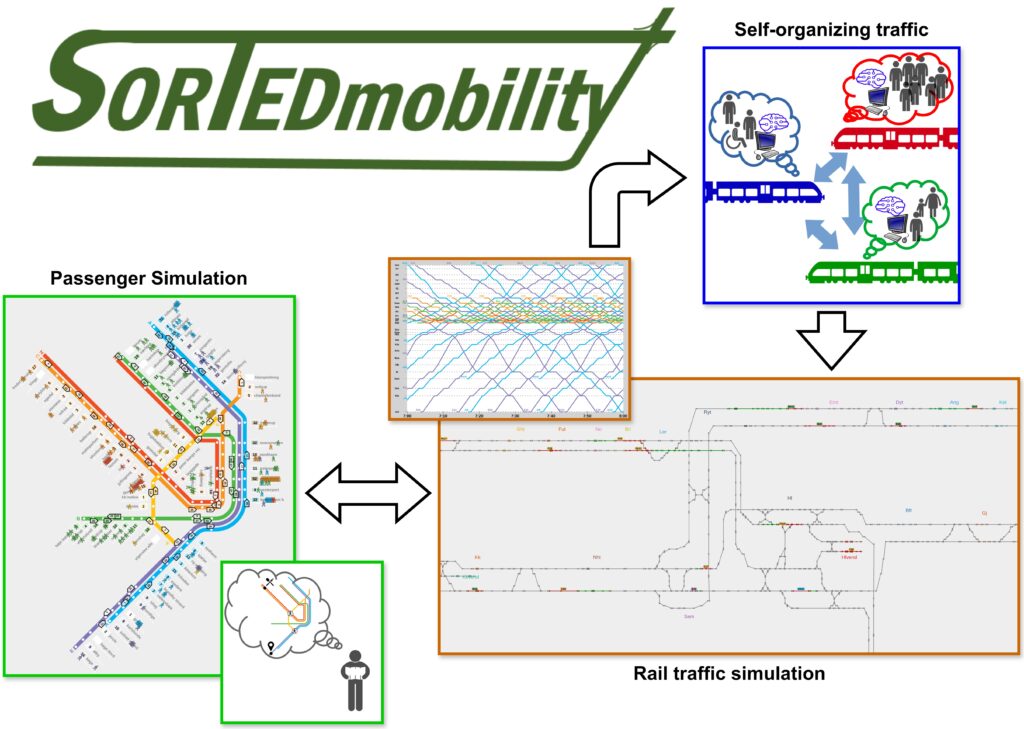

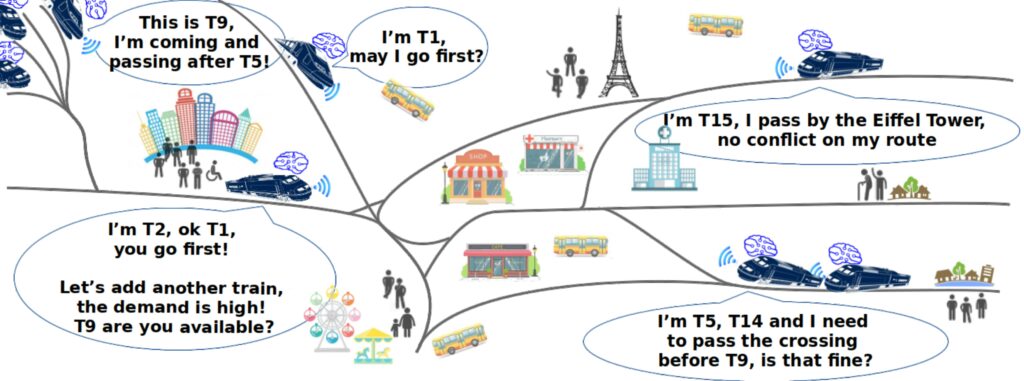

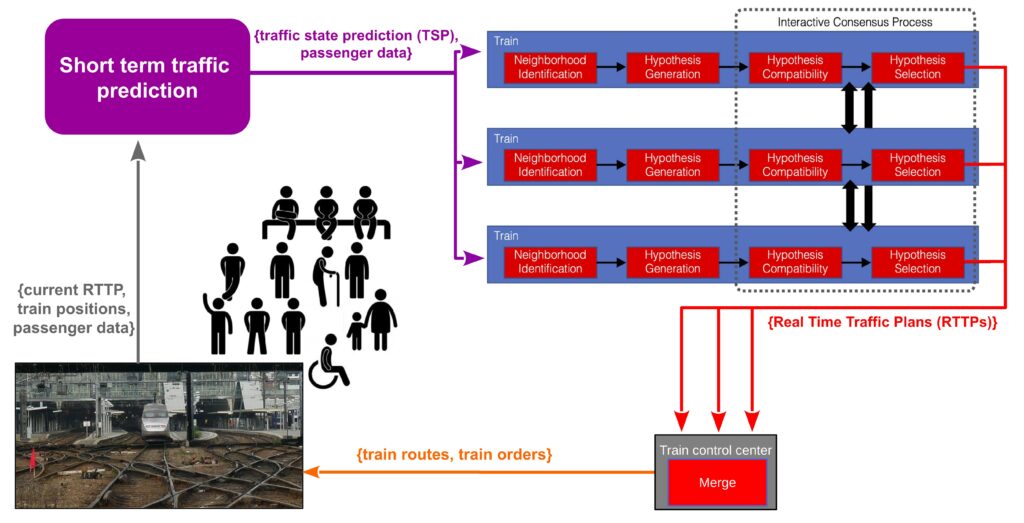

In this self-organised system, trains would communicate directly, making local decisions about priorities and platforms without central control. The project developed a sophisticated testing environment combining mathematical optimisation with simulations. “Every detail of railway infrastructure and train movements is represented,” Paola says, including train weight, length, and acceleration curves.

Within Sorted Mobility’s autonomous system, trains use a consensus system inspired by artificial intelligence models when delays occur. Each train maintains a list of preferred options but doesn’t need to reveal why it prefers certain choices—crucial for maintaining commercial privacy. If trains can’t reach an agreement, they default to their original schedule, ensuring system stability.

Testing Across Diverse Railways

The project tested this concept in distinctly different scenarios. One was a busy Italian line between Pioltello and Rovato, which is 54km long and carries both freight and passenger traffic. Here, researchers examined how self-organisation could work in a competitive environment where multiple operators share a track. Running simulations with over 75 trains in a five-hour period, they found the system could maintain overall performance while protecting operators’ commercial interests.

“Most trains could be a bit happier without worsening system performance and keeping their private information,” Paola notes. This proved particularly valuable for freight operators, who might not want to reveal the importance of specific shipments but still need to negotiate priority.

In France, the team studied a rural “capillary” line between Guingamp and Paimpol, which is 37km long with a movement of 150 passengers and sees 21 trains every five and a half hours. Here, they found that self-organisation could maintain service quality while potentially reducing operational overhead. “These types of lines are very critical in France and other similar countries,” Paola explains. “There must be a way to operate them with minimum costs while maintaining service.”

The single-operator environment allowed researchers to focus on passenger benefits. They discovered that trains that could use their own passenger counting data to make decisions achieved better outcomes than centralised systems that lack access to this information due to privacy barriers.

Tackling Urban Complexity

The most ambitious test came in Copenhagen’s suburban rail network, comprised of 170km of a star-shaped urban network with multiple travel operators and over 16000 passengers using the system in the three hours of the morning peak. Here, researchers integrated passenger prediction into the decision-making process. Using a sophisticated population model incorporating socioeconomic data, work patterns, and travel habits, they created the first-ever system of this kind that considers how railway performance affects passenger route choices.

“We predict demand flows considering the impact of railway traffic on passenger choices,” Paola explains. “If I’m a passenger, I’m going to check my travel app and decide based on what lines are working. This had never been done in the literature before.”

While time constraints limited the full exploration of this approach, initial results suggested significant potential. The team observed that looking 20 minutes ahead in passenger predictions could inform better decisions, though they also identified challenges with “border effects” when significant events occurred just outside their prediction window.

Trains Take the Wheel: How Autonomous Systems Could perform as well as the Status Quo

Across all three contexts, self-organised systems performed comparably to traditional centralised management while offering distinct advantages. Beyond maintaining privacy and improving passenger service, self-organisation could help solve the scaling challenges that plague current systems.

“The problem of scaling up decisions is very real today,” Paola notes. While centralised systems struggle with more extensive networks, self-organisation’s local decision-making approach could naturally handle network expansion.

However, implementation faces significant institutional and legal hurdles. As Paola explains, “We probably won’t have a fully self-organised system soon, but we could start thinking of hybrid systems where trains make some decisions.” The project’s final round table, which included representatives from Deutsche Bahn, Network Rail, and other European railway infrastructure providers, endorsed this gradual approach.

Rural lines might see the first implementations. “Changing the system in these isolated lines may be easier, operated by a single operator where problems are less critical – we might see change there within five to ten years,” Paola suggests. Success in these environments could pave the way for broader adoption.

Building Better Assessment Tools

Perhaps equally valuable to the self-organisation concept itself, the project developed sophisticated assessment tools combining optimisation, simulation, and passenger modelling. This framework allows for a realistic evaluation of any traffic management approach, whether centralised or self-organised.

“What we started doing was a very original contribution,” Paola notes. “We predicted demand flows considering the impact of railway traffic on passenger choices. This opens up crucial questions about how people would react to smarter systems. Would they use them more?”

A Model for Future Research

Beyond its technical findings, the project demonstrated the value of allowing truly exploratory research in railway systems. “This was amazing,” Paola reflects. “We had actual collaboration between academia and industry without needing to end up with a commercialised product. We were really doing pure research.”

This freedom allowed the team to investigate a concept that could reshape railway management thoroughly. While full implementation remains distant, the project proved self-organisation’s viability and identified promising paths forward through hybrid systems and targeted deployment.