Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

The Rise and Fall of Urban Manufacturing

For as long as there have been cities, they’ve been centres of production.

Starting with the natural materials of wool, wood, and leather, we added metals, ceramics, and glass, and arrived at plastic, chemicals, medicine, and microchips. Bread, brewing, and bookbinding have always been consistent staples. Walking through the streets of yore, we would have witnessed artisanal families living and trading from homesteads rooted in their communities, highly skilled smiths training apprentices, and districts dedicated to single activities like cobbling or tailoring.

With industrialisation came new produce and new processes for making familiar goods. The lure of jobs during the Industrial Revolution created mass migration to and growth of 19th-century European cities. Manufacturing created economic prosperity, which continued largely until the post-war period.

Since the 1960s, the ‘clean’ service sector has overtaken as the dominant economic presence. The personal wealth of service sector workers made private transport possible; people could now live in pleasant green suburbs and travel further to work at their convenience. Makers were pushed out of urban centres and away from supply lines, markets, and labour as their activities were deemed incompatible with residential space.

It’s a grim summary. However, urban manufacturing persists. Its legacy is largely down to the following cultural and geographical fixtures that endure.

Industrial Commons

A historic city’s manufacturing landscape draws heavily from its knowledge and skills, or industrial commons, developed over time. Innovations stemming from these wouldn’t necessarily occur in other locations, where know-how differs.

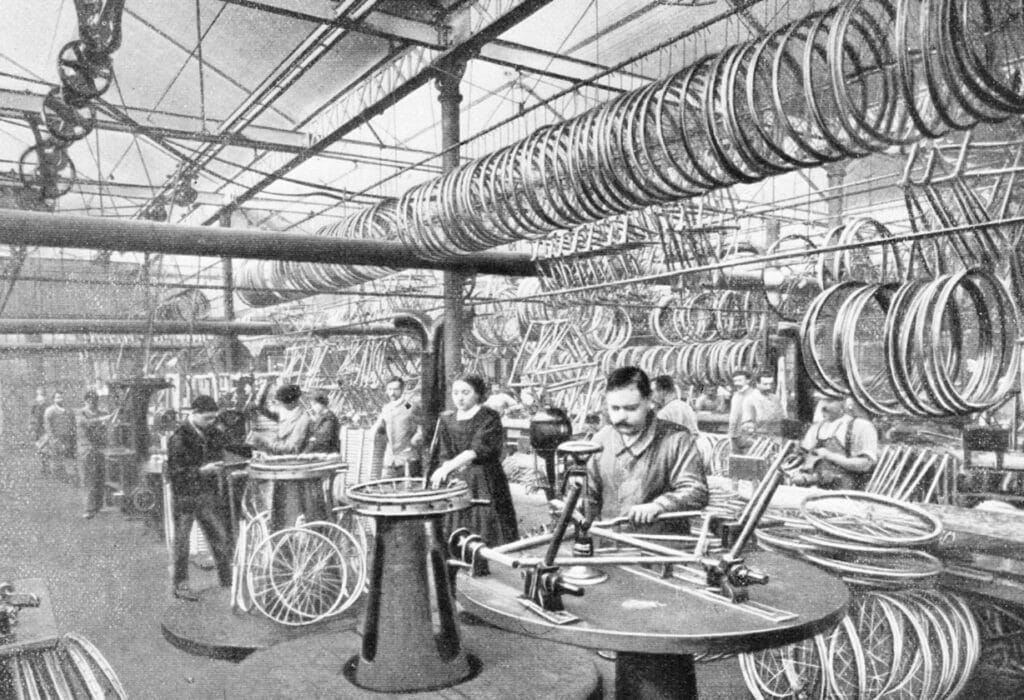

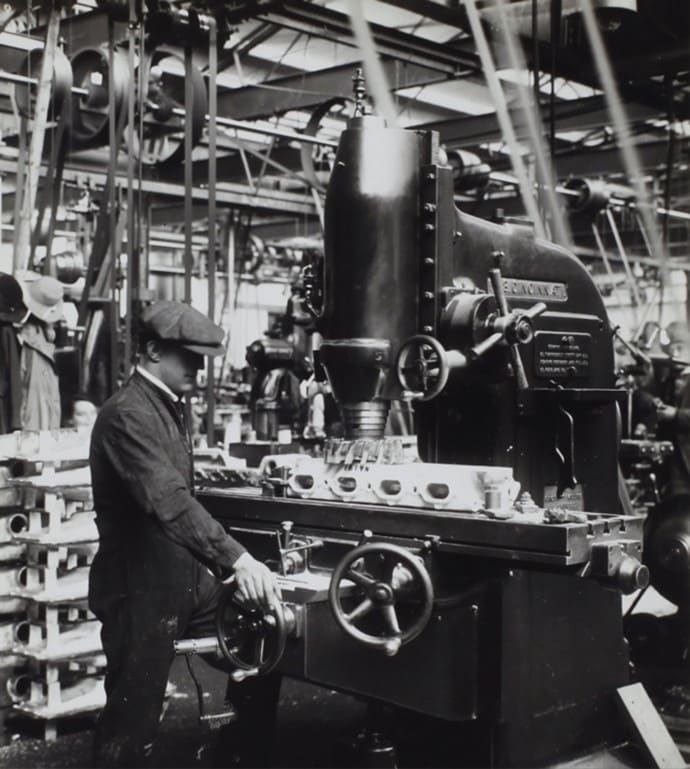

For example, bicycle production in Coventry in the UK stemmed from the expertise of watchmakers and the weaving industry. This led to the foundation of car construction. Brussels’ pharmacies spawned their infamous chocolate-making. And in Italy, who would have thought Bologna’s own automotive industry has roots in the Middle Ages? But this story begins with the knowledge derived from silk production hundreds of years ago.

This progression is a modern phenomenon, too, as making links closely with services and design. Old Street in the Maker Mile is home to London’s Artificial Intelligence scene, a hub where computer parts production lies smack bang in the established software development district. The unique fabric of a city’s industrial commons gives it a competitive edge.

The evolution of manufacturing in Coventry, UK. Image credit: Oliver Hörzer

Labour

Attracting workers with jobs in its cotton industry, Manchester in the UK swelled to four times its size in the 60 years to 1861. Dense populations in European and North American cities provided very localised pools of labour and consumers. But the sprawl of homes needed to accommodate workers took people further and further from centralised working districts; retaining skills in short supply became a major problem.

Henry Ford famously exploited division of labour to build his car manufacturing empire, but it was Adam Smith who coined the term in 1776 after observing how individuals repeating single tasks accelerated production. Workers no longer required extensive training for making complex goods from start to finish. Fewer people took up traditional trades. Production was no longer confined to a place with particular knowledge, driving relocation and offshoring.

Servification and automation since the 1970s have created new threats to manual jobs. But we’ll always need muscle and talent. Businesses have undergone a process of hybridisation: incorporating research, design, production, and sales: the 21st-century heralds the age of a pluri-disciplinarian workforce: those who are adept at performing automated and manual tasks.

Even when a product is fundamental to the functions of a city, there may not be any profit to be made from it. NGOs and community groups pick up the slack in the guise of running projects that train marginalised members of the population who “face difficulties to find sustainable work (such as the disabled, migrants and ex-convicted felons)”. Oddly, the push for inclusion poses a new challenge: measures are needed to prevent the exploitation of a vulnerable labour force.

Technology

Competition amongst makers accelerates innovation and technological advancement. Less present are gigantic looms and immovable printing presses. Urban manufacturing became more flexible with a decrease in equipment size and increase in quality and efficiency. Good for production, but not necessarily for creating highly skilled jobs at scale.

Twenty-first century producers are predominantly small- or medium-sized enterprises of one to five people. Increasingly, they are isolated micro-manufacturers or ‘hobby makers’, working in small spaces, producing at home, and trading online. As Cities of Making found, in London, few companies create the nuisances people associate with heavy traditional industry.

Digital marketplaces and 4.0 technologies enable individuals to create at home. Distributed manufacturing and mass-customisation are staples of the modern making movement, with additive manufacturing and laser cutting among those technologies giving a new spin to traditional skills and artisanal crafts. As stated in Foundries of the Future, goods can be customised fairly cheaply “without altering production processes”, meaning companies can easily and affordably “match supply to the demand”.

Trade and Transport

At first, nature commanded the urban landscape. As time passed, humans manipulated it to suit their needs. Manufacturers influenced the make-up of cities. Canals were dug. Roads were laid. Railways roared in, bringing resources and people. As we again strive for today, Mediaeval times and the Industrial age saw workshops spring up alongside roads and waterways, combining trade with connectivity.

Entrepreneurial makers are once again looking at importing and exporting goods by barge. To revitalise small-scale making, Cities of Making recommends a return to the high street to provide better access to markets, or clustering similar producers in a specialised district with a set of shared resource needs. “For example, metal smiths performing similar but complementary tasks may have been located near a canal to access heavy raw materials and fuel.”

Home-to-Work Arrangements

Access to jobs by interconnected soft modal means, as seen in the London borough of Haringey, is a boon for environmentally conscious and low-paid workers. Ignore the car lobby: walking is the oldest form of transport and remains popular. Cities can empower people to take alternative means of moving by creating safe pedestrian and cycle zones.

Small-scale manufacturers need regulations that support working from home, protecting them from undue complaints from neighbours. Plus, it eradicates the need to travel altogether. Great for the environment!

Practicality

Mixed-use neighbourhoods were once the norm. These days, we’re sceptical of noise, pollutants, smells, and traffic. But it’s often unfounded, and mixed land use brings jobs closer. At other times, manufacturing and residents simply have to co-exist.

Olympic Park was the focal point of London’s 2012 summer games. There’s plenty of housing in the district and, along with it, a cement works. The local construction sector needs this nearby: it’s a race against the clock before cement sets, so distances are limited by chemistry. Bread makers encounter similar shelf life and time-limited producer-to-consumer challenges.

City administrations can ease tension between land users. As identified in Haringey, council-led improvements to road cleanliness and maintenance paid for by business rates create a positive quality-of-life link to having manufacturers nearby.

A New, More Responsible Era

Since the Industrial Revolution, cities have been choking skies with bellows of soot. Despite attempts at onshoring, considerable imports and exports now hinge on air travel. In response to the carbon emissions that manufacturing produces, public pressure, environmental acts, taxation, and low-emission zones have contributed to its decline.

Advances in equipment and transport, such as 3D printing and electric vans, reduce the maker community’s carbon footprint and garner favour from an eco-friendly client base. They are often willing to pay more for customised, quality, and conscientious produce, underpinning manufacturers’ capability to meet expectations. We’ll see more electricity-powered deliveries in the near future as cargo bikes, scooters, and drones tackle last-mile connectivity. But beware: such advances may be held back as regulation and policy struggles to keep up with the pace. Political leaders must work with producers to create a synergy that reinforces manufacturing’s basis within contemporary cities.

“Where the process is new or rapidly evolving, such as in nanotechnology, researchers and makers need to work together to understand how the technology can be used in real-world applications, where the value will be created.”

Urban Manufacturing Through Time in a Nutshell It would be misleading to think any decline in manufacturing activities and employment is an indication the sector is in its death throes. This is merely a transition in an ever-changing picture of production that has continued since making first emerged. It has created, shaped, swelled, populated, fed, clothed, educated, paid, and polluted cities. Technology has caused a decrease in labour intensity but not in the need for produce. Manufacturing is here to stay, and by acknowledging the successes of the past, we can determine how to best reintegrate making around us in the years ahead.