Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

If policy makers are provided with decision-making tools that reduce the complexity of food, water, and energy systems, they can integrate these systems to improve circularity and sustainability in urban areas. According to results from the CRUNCH project, decision makers will only succeed with this if they embrace co-creation and public engagement. The project’s coordinator, Alessandro Melis, tells us about the impact of their Integrated Decision Support System (IDSS), and how they created it.

When urban policymakers approach the daunting task of integrating a city’s food, water, and energy system, they are faced with a great deal of complexity which could potentially overwhelm them. To avoid such problems, the CRUNCH project is developing an Integrated Decision Support System (IDSS) for policymakers that focuses on integrating the food, water, and energy systems in cities. The system will provide policy makers with a clear quantitative overview (on a digital platform) of how their cities’ food, water, and energy systems operate and what kind of changes to one system affects another one.

“The IDSS shows so much promise that the municipality of Uppsala are planning on using it for the development of new neighbourhoods responding to their local population growth.”

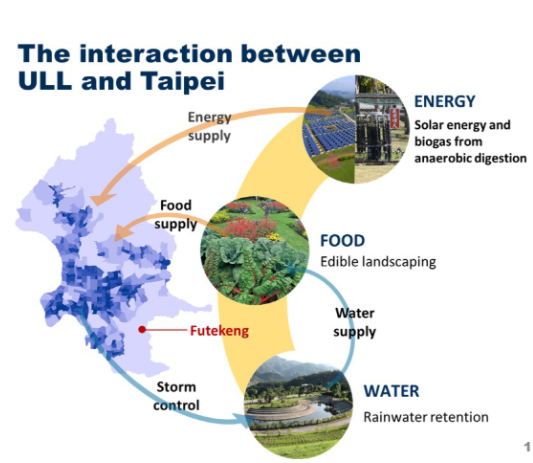

Two core elements of the project is the understanding of how urban design and citizen engagement can positively impact food, water, and energy integration. The project is achieving both core goals by using the Urban Living Lab (ULL) methodology. This method creates physical spaces in cities to work with citizens to co-design urban design solutions and to gain data about how they feel about a range of proposed urban design choices and solutions for their city. Therefore, the project has both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. On the one hand, the project is generating useful numbers for policy makers, such as how much energy can be generated with solar panels with a given building design in a particular climate, informing them what kind of urban design choices are optimal, and on the other hand, it is seeing how citizens react to certain design changes through the ULLs.

Due to the complexity of the project, the six partner cities work on different aspects of the project. The team in Uppsala, Sweden has created the IDSS tool, the initial version of which is already accessible online. Whereas the Eindhoven team, in the Netherlands, is responsible for the codesign survey used in the ULLs to gather relevant data from citizens. In Gdansk, Poland the project is specifically gathering data on what kind of urban design changes have a positive impact on the food, water, and energy systems of a city.

In Taipei, Taiwan, the project is examining the kind of remediation processes that can be used to turn a large landfill into an urban farming area. Whilst in Southend-on-Sea, the U.K., the project has put together a panel to decide how best to use recycled plastic for urban furniture; Zero Mass Water panels (ZMW) – solar panels that convert air into drinking quality water. Two of the three nexus areas (water and energy) are covered by this technology.

In Miami, Florida, the project operates on the city scale to see how urban design changes could combat sea-level rise. All these elements will come together to refine the IDSS. Despite it still being in the refinement process, the IDSS shows so much promise that the municipality of Uppsala are planning on using it for the development of new neighbourhoods responding to their local population growth.

Alessandro believes that if the project is successful, urban design can be done in a much more sophisticated way. He argues currently, urban design thinking does not have precise enough data on how food, water, and energy systems can create synergies. The project’s IDSS could significantly mitigate this issue. He talks through one specific example: if a building were to install solar panels on its rooftop, then batteries would be required since only 25% of solar energy can be used directly. However, rainwater can be collected to create a dynamo for a building’s solar energy system. The IDSS would allow any policy maker to see how much water would need to be collected and if this were feasible in this case. He is quick to add, “the scope, of course, is not about writing rules for one building but for creating city-wide policy that a mayor or high-level policy official knows works for their city.” What may be particularly noteworthy, is that that the project’s results are having an impact on a regional scale. The Charter of Resilient Communities, in Italy, has based many of its articles on the qualitative work produced by Crunch. Elements of the project have even been adopted by the state of Campeche in Mexico for a research study they are currently conducting.

Alessandro Melis

“It is not about writing rules for one building but for creating city-wide policy that a mayor or high-level policy official knows works for their city.”

Another strength of the IDSS lies in its simplicity. The project claims that existing tools typically require a week of training in the best-case scenario, whereas CRUNCH’S IDSS does not. This is because their IDSS relies heavily on machine learning models that are invisible to the user. This permits the user to simply play around with different innovations in their food, water, and energy systems in an intuitive manner without worrying about complex calculations. Despite its simplicity, the IDSS is still able to reflect highly local conditions. This is evidenced by the fact that all six ULLs, which all represent very different environments, have been able to successfully use the IDSS for their local context.

The Charter of Resilient Communities, in Italy, has based many of its articles on the qualitative work produced by CRUNCH.

The project has already generated significant data that is impacting other projects and government actors. In particular, Alessandro thinks the use of computational modelling to tackle sea-level rise in Miami is on a scale not seen before. He does add that it is important to note that they are still analysing a lot of the data from the project, so more conclusions are still to be made. Nevertheless, he is confident that much of what they have learnt is transferable. He tells me, he has now started a new research project on the islands of Granada and Dominica where they are redesigning their cities to be resilient against hurricanes. He says because of CRUNCH, “I can tell exactly what the important indicators are.” He is also confident that the IDSS can be adapted for use in this new project. the project’s results are having an impact on a regional scale. The Charter of Resilient Communities, in Italy, has based many of its articles on the qualitative work produced by Crunch. Elements of the project have even been adopted by the state of Campeche in Mexico for a research study they are conducting.

Although the project has been successful in gathering a lot of quantitative data, it has also shown the need for high level engagement with citizens. Alessandro offers an example for why this is the case by telling a story from the project’s meeting in Eindhoven. They were discussing a local initiative where a park had taken an area previously covered by grass and turned it into a more biodiverse and semi-wild environment. Despite indicators showing that this was a success in terms of water management, biomass usage, and biodiversity, residents of the local area had a negative perception of this area of the park and perceived it to be poorly managed, as they were accustomed to neat cut grass, managed hedges, and paved spaces. However, dialogue and a slow and careful approach helped to overcome initial reservations over greening.

“Instead of adding ecological elements on top of the urban landscape, we can design the urban landscape to be intrinsically ecological.”

Alessandro predicts that the long-term impact of the project is showing that it is possible to develop tools for policy makers that control the complexity presented by integrating food, water, and energy systems. He has a strong conviction that if these systems can be integrated and the public are engaged in the process, then a transition can be made where instead of adding ecological elements on top of the urban landscape, instead we can design the urban landscape to be intrinsically ecological. He goes on to emphasise just how urgent this issue is by pointing to the fact that the mass of man-made objects is now equal to the mass of all living things. Therefore, it is essential to overcome the complexity of integrating food, water, and energy in cities: “if we solve this problem of complexity, we solve the problem of the survival of humanity.”

>> Learn more and contact CRUNCH

This is one article in a series of result interviews with SUGI projects in 2021. More articles are to be published. The Sustainable Urbanisation Global Initiative (SUGI)/Food-Water-Energy Nexus is a call jointly established by the Belmont Forum and the JPI Urban Europe. The cooperation was established in order to bring together the fragmented research and expertise across the globe to find innovative new solutions to the Food-Water-Energy Nexus challenge.