Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

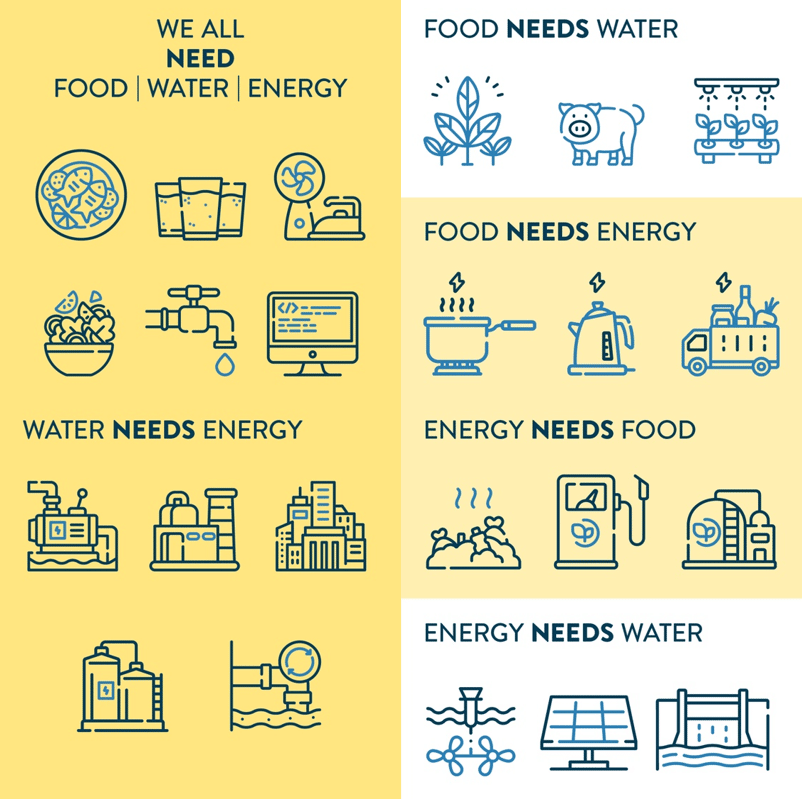

Almost everything we do has consequences for the environment. This is certainly true for our part in the food-water-energy nexus; generally speaking, we are net users of each of these three resources. If we have a clearer picture of how these are interdependent, and the ramifications of not viewing them as such, we can put appropriate controls in place. Ideally, this is the role policy plays. But effective policy must be fed by facts.

Information and communication technology may hold the key to understanding the nexus in the context of cities and for developing governance that tightens our grip on managing resources. Could it be that data is the secret ingredient to true FWE sustainability?

Rising urban populations are forever adding pressure to strained resources. There will be no let-up. We need to learn to manage the situation – and food, water, and energy – better.

Sustainably managing the resource interdependences will be one of the 21st-century’s main challenges and will affect how cities develop over the next decade.

Steffen Lehmann

Businesses, says Andy Wales, should pay fair prices that account for the scarcity of raw materials in their value chains. Hitting industry in the pocket sharpens focus on an only-use-what’s-necessary consumption motif. But realistically, if companies are to change, they require support from the top.

Policy needs to be joined up. Ingrained silo thinking holds this back, persisting with separate and conflicting strategies for the three strains of the nexus.

This is extremely short-sighted. According to the UN’s Economic Commission for Europe, FWE are so unfathomably intertwined that “actions in one policy area commonly have impacts on the others”. The upshot is this: define integrated policies or forever we’ll be putting out fires.

A factor to consider in policy is also the role of assumption. With respect to energy as an entry point, the Austrian Development Corporation highlighted the focus we have on electricity. Energy spans far greater realms in the nexus. It provides heat and fuel for cooking; in developing countries, this may originate from burning wood or dried dung. Policy should account for variety and regional social and environmental conditions.

A report from the European Centre for Development Policy Management listed among its recommendations “improving the interface between complex scientific knowledge and political decision-making”. Similarly, in increasing understanding of the nexus, Keidai Kishimoto and Wanglin Yan highlight how “it is important to design, plan, and implement areas based on evidence”. The areas in question are our three friends: food, water, energy.

There’s a consensus here. And not just around informed city planning. Data holds the key to communicating the nexus to the uninitiated, too.

Steps to bridge scientific and policy arenas “includes using mixed teams,” writes Alfonso Medinilla, and analysis “through visualization, storytelling, communication tools and media engagement”. Angela Morelli tapped into this idea when using simple graphics to depict the extent of our virtual water consumption. It’s easy to follow and stops you in your tracks!

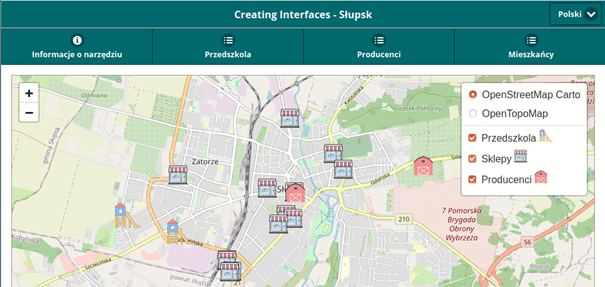

Pia Laborgne and Iulian Nichersu from Creating Interfaces corroborate this idea, adding that maps “and participatory modelling help people relate to the idea of a nexus”. That’s just the point. If anyone – top-down or bottom-up – is going to engage in the sophisticated nature of the nexus, we need to stimulate a personal connection. That’s how we generate more sustainable habits among the populous and generate buy-in for our joined-up policies.

Alfonso Medinilla doesn’t overstate the political responsibility in “articulating nexus problems and solutions”. This FWE expert is spot-on in calling for “continuous translation of technical data for use in policy-making”. But we have to make it simple for everyone to understand. Like a story.

Diverse ranges of data dropped into interactive story maps interpret the nexus’ complexity into a simple and locally-relevant narrative.

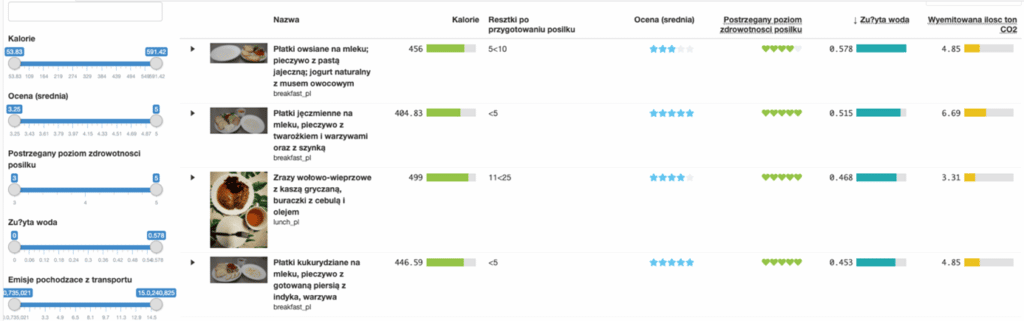

Creating Interfaces’ dashboards represent the carbon and water footprints involved in producing meals.

These are powerful tools for individuals and organisations who are environmentally conscious but lack the time and scientific expertise to delve into cumbersome datasets. Parents of the children in kindergartens in Slupsk, for example, get to see details of children’s lunches, including nutrition, ingredients, calories, waste, and place of origin. This gave them the power to decide what they deem to be healthy and ecological enough for their children to eat.

But where do we get this data in the first place?

Andrea Pierce notes the difficulties standalone cities face in terms of FWE governance. Take western Europe importing fruit from South America and piping gas from Siberia, for example: the nexus reaches a regional, national, even international scale. This limits a city’s capacity for control.

Data feeds offer some respite. People provide the details.

Establishing feedback mechanisms is key, says Steffen Lehmann: we face “a critical need to equip decision makers with evidence from research” and the tools to gather and interpret it.

Creating Interfaces enlisted the help of the public via a series of participatory workshops in what is known as an Urban Living Lab.

This co-creative approach acknowledges “that citizens themselves are best placed to represent their own needs, meaning they can contribute to transformative research when included”. In their case, data gathering embraces a public-friendly format, an app, where people in two cities – from utility companies to local grocers to residents – enter information about their lived experiences:

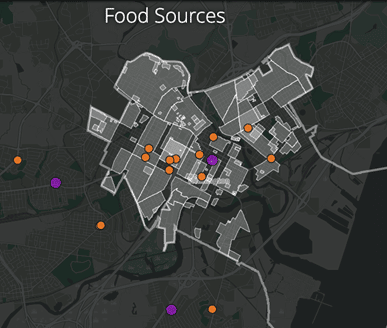

When drafting strategy, we should consider the entire nexus, not see each domain in isolation. Geographical Information Systems (GIS) enable us to overlay multiple layers of data in a spatial context, forming a realistic model of the nexus in action in a given location. Creating Interfaces did this to map water, food, and energy sources in Wilmington, USA.

The GIS map-based interface makes relevant information available to and digestible by the public. Policy writers access it as an invaluable resource.

The CRUNCH project developed an Integrated Decision Support System (IDSS). As with all effective nexus engagement platforms, this is built on the basis of visualisation: literally showing policymakers “how their cities’ food, water, and energy systems operate and what kind of changes to one system affects another,” reports Alessandro, the project’s co-lead.

In conversation, he tells us that the purpose of a data-driven tool like this is “to see how we can transfer the complexity” of the FWE nexus into “understandable and manageable decision-making”.

Human and environmental forces pull the domains of food, water, and energy in a forever-shifting kaleidoscope of supply, demand, generation, and use. As a species – and as frequently proven in substandard policy – we lean towards rigid solutions because fluidity is difficult to legislate for.

A blend of quantitative and qualitative details helps to build a vision of the local nexus anyone can comprehend. This should take the form of collating and interpreting real numbers – measurements such as a city’s energy production and consumption, or an administration’s costs and savings from stringent resource management – but also experiences and opinions of city stakeholders via surveys and interviews.

Ongoing data gathering generates an increasingly reliable snapshot of a city ecosystem constantly in flux. As Alessandro continues, we should “avoid the ramification of prejudice” with depth and breadth of data. In other words, the more we know based on the most diverse input we can muster, the less risk of unreasonable bias we face. Iterative thinking and design work like a charm to enhance the tools we rely on to inform impactful policy.

Inger Andersen, Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme, stressed that in “terms of digital tools for the environment, we have progressed in monitoring platforms, but more is needed to influence behaviour,” strengthen the impact, and “inform decision-making”.

The tools we’ve mentioned are a step in the right direction, but no two cities have the same pattern of stakeholders, businesses, resources supply and demand, geography, economy, politics, policies, and trade. Digital tools are only as good as the data we input.

Strictly speaking, that means starting with a blank canvas at each urban location. Creating Interfaces’ tools are open source. The IDSS, Alessandro tells us, is designed to be shared and replicated. This is a start, but resources such as these need people in place with the knowledge and motivation to set them up locally – possibly in the city administration. And it requires the will of stakeholders to input information. Communicating their benefit is a must.

This is only the start of the journey but thankfully it’s gaining traction. Alessandro mentions Uppsala in Sweden, where authorities have taken the IDSS and ran with it, incorporating the tool into planning new neighbourhoods in an expanding city. Suddenly we’re seeing the FWE nexus as a building block rather than an afterthought.

All being well, this will be the norm in the future. If we work with people and data to inform policy, we can build cities around a comprehensive understanding of the nexus and wave goodbye to sticking plater solutions applied when the cracks emerge.

This article is part of a pilot effort between CityChangers and JPI Urban Europe to highlight the complex interrelations of urban food-, water- and energy systems to a non-academic audience. The articles are based on interviews with researchers from five of the 15 projects funded in the SUGI FWE Nexus, reports produced in the SUGI FWE Nexus initiative as well as public statistics and reports. The conclusions and recommendations derive from the authors conclusions. Read more articles and access research results from all SUGI FWE Nexus projects at the Urban Europe website.