Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

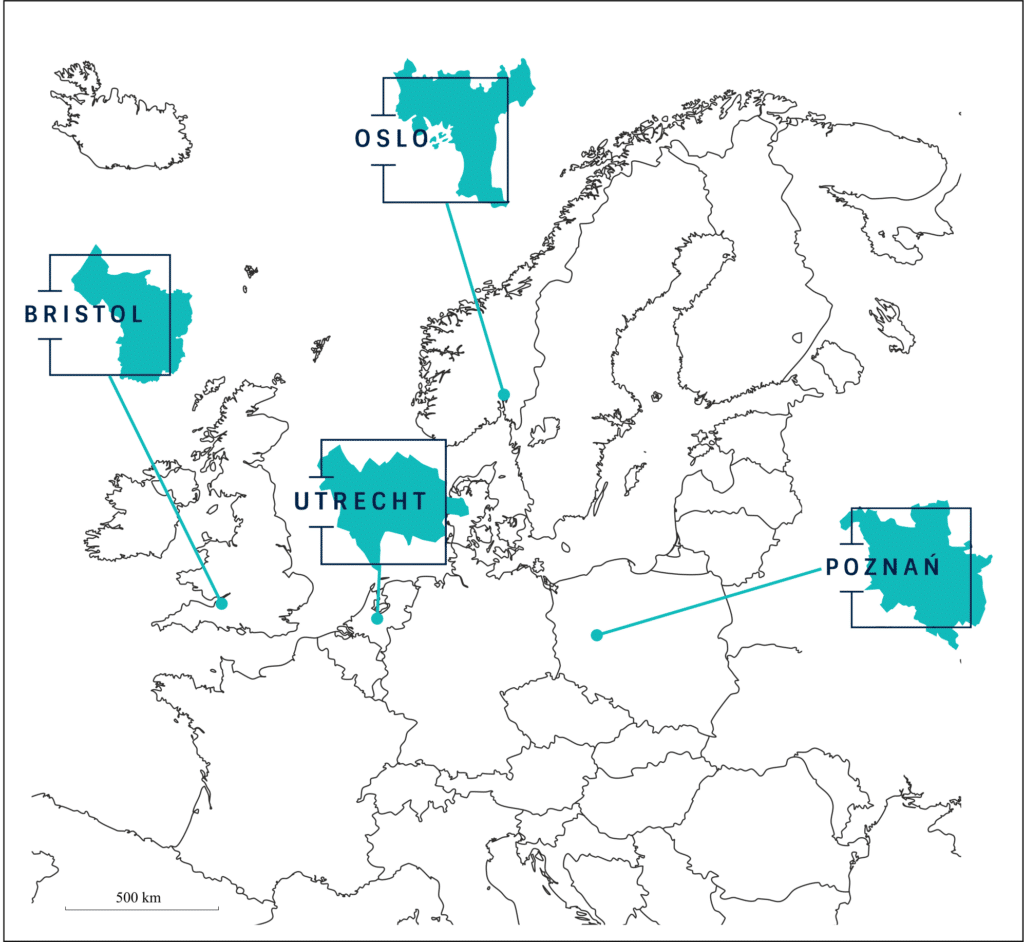

Working across four European cities – Oslo, Utrecht, Bristol, and Poznan – researchers have uncovered crucial insights about fairness in transport electrification. We spoke about the findings with Lars from the Institute of Transport Economics in Norway, the ITEM project’s coordinator, and Hannah from the Transport Studies Unit at Oxford University, which led much of the policy analysis work.

Beyond Environmental Benefits

“There has always been a lot of emphasis on the environmental benefits,” explains Lars. “We believed it was time to also look at social dimensions, especially when we are advancing towards larger levels of uptake.” This shift in focus revealed important gaps in how cities approach electric mobility.

Through an analysis of over 50 policy documents related to transport electrification and interviews with 50 local and national policymakers, representatives of those delivering and using electric mobility services, and other stakeholders across the project’s four cities, researchers found that while environmental goals receive considerable attention, social inclusion often takes a back seat. The project team deliberately avoided pre-defining what “inclusive” meant, instead learning from stakeholders through a series of workshops. This approach revealed unexpected gaps in current policies and highlighted tensions between environmental goals and social considerations.

Understanding Household Needs

ITEM conducted approximately 25 household interviews per city, carefully selecting both users and non-users of electric mobility, including socially and economically marginalised groups. The research revealed significant disparities in adoption patterns. In Oslo, for instance, researchers found higher electric vehicle uptake in higher-income areas and among single-family homes, highlighting how housing type affects adoption. Also interesting to note is that while in Bristol and Poznan, the transition to electric vehicles is led by fleet and business vehicles, in Oslo, it is actually dominated by private car ownership.

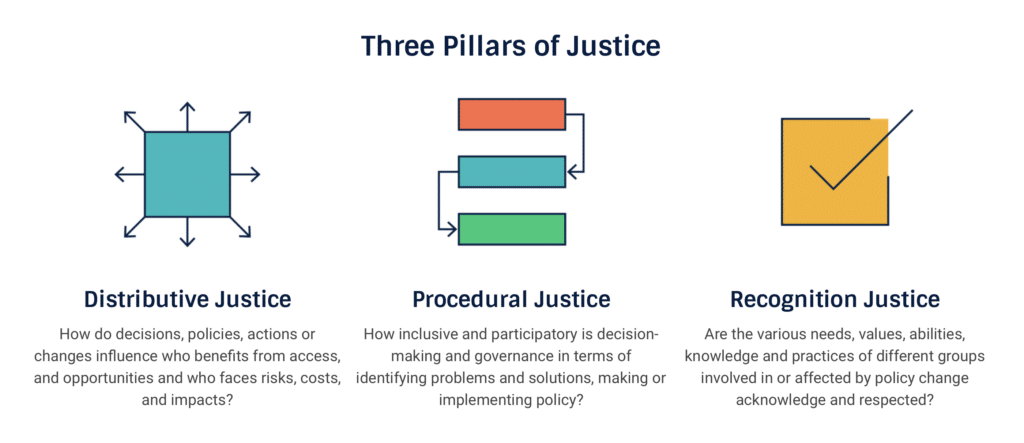

The project identified numerous barriers beyond simple cost considerations. “It’s not just about economic costs,” notes Lars. “When it’s about recognition justice, it’s more about how it feels for people, maybe how they express that electric mobility is something for the rich.” Digital barriers proved particularly significant, with many respondents expressing concerns about complex charging systems and app requirements, which may hinder some groups in particular, such as older adults, those without smartphones, and those who are less tech-savvy.

The research revealed how awareness differs between cities at different stages of transition. “In Oslo, where this transition has come much further,” Lars explains, “people are much more familiar with all the policies and benefits. Even non-users are closer to imagining themselves adopting an electric vehicle or electric mobility solution.”

Comprehensive Policy Analysis

One of the project’s most valuable contributions has been helping cities understand their complete electric mobility policy landscape. “Even though they [policymakers] work with it daily, that overview didn’t exist anywhere,” Lars explains. “We had to scrape it together from all kinds of different documents, websites and other media.” This comprehensive overview proved extremely valuable for policymakers, helping them identify gaps and contradictions in their approaches.

In the final workshop of three held in each city, the project brought together diverse stakeholders to evaluate policies. Hannah describes their approach: “We had them rate policies on a seven-point scale, but they also had to rate how confident they were in their assessment.” This method helped identify knowledge gaps and areas where different departments could better coordinate their efforts.

The evaluation revealed fascinating patterns. In Bristol, for example, e-scooters and e-bikes scored highly on distributional justice, while private and shared electric cars showed room for improvement. The research also identified significant tensions between national and local approaches. “There’s quite a lot of tension between national and local government ideas around electric mobility. Some national government policy is overly focused on private EVs, overlooking all the other things that make up the urban transport system,” Hannah notes. For policymakers interested in further understanding this tension, Hannah has produced a paper elaborating on these findings.

Overlooked demographics

While the project initially anticipated certain groups would feature prominently in discussions about inclusion, the research revealed surprising gaps. “When we spoke with policymakers, low-income and disabled groups came up quite a lot,” Hannah explains. “But what was really interesting was who didn’t come up.” Gender considerations, for instance, were less prominent than expected in electric mobility discussions.

The research also highlighted significant variations in how different cities approach electric mobility. In Poznan, researchers found more debate around whether electrification should focus on public transport rather than private or shared transport options. The Polish team achieved particularly strong stakeholder engagement throughout the project, demonstrating the importance of local networks in policy development.

Policy Tools and Recommendations

The project is producing detailed policy briefs for each city, with Bristol’s already published. These briefs provide comprehensive evaluations of current policies and specific recommendations for improvement. The evaluation framework considers multiple aspects: coherence of instruments (how well different policies work together), consistency of goals, and alignment between goals and instruments.

A key finding emerged regarding implementation speed and public acceptance. The research suggests that while climate change creates urgency, sustainable transformation also requires careful consideration of local contexts and community engagement.

Ageing Society and Future Transitions

The project also examined how electric mobility transitions interact with broader societal changes, particularly in ageing populations. This work, focused especially on Norway and Poland, explored how demographic shifts might affect mobility needs and adoption patterns. This research stream continues to develop, promising valuable insights for future policy development.

Building Better Policy

Through its combination of household perspectives and policy analysis, ITEM provides cities with valuable tools for evaluating and improving their electric mobility initiatives. The project demonstrates that creating inclusive electric mobility systems requires careful attention to multiple forms of justice – distributive (who gets access and where), recognition (whose needs are considered), and procedural (who gets involved in decision-making).

“We started with that first workshop asking what justice and inclusiveness mean and how it can be part of policy,” Lars finishes by saying, “We don’t want to use justice and inclusiveness to slow down the transition or go back to fossil fuel vehicles. It’s about uniting that element of fairness and inclusiveness with environmental goals.”