Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

Mechanisms for Integration

Arrival infrastructure is the basis on which migrants navigate the geographical and systemic facets of a city, laying the foundations for their newly forming sense of place and belonging.

Implementing the right policy structures that govern this can support and ease the integration process, and set migrants up as independent, empowered contributors to society.

As a starting point, important information should be available city-wide in a range of formats: multilingual, digital, and analogue.

Local language comprehension is key to inclusion and social connection, navigating official processes (including applying for residency), the search for housing, accessing healthcare, job hunting, and establishing basic social security. Informal translation is unreliable, so language courses should be made available to anyone, regardless of their legal status.

Language learning is a slow process, so professional interpretation should be made available to public-facing services such as healthcare and legal advice. This might be necessary for migrants appealing a failed asylum claim, for example.

To get to where they’re most needed, interpretation services need to be available to practitioners across sectors on an ad hoc basis. Simple request procedures would encourage staff to use it. But first, they must be fully informed about the availability and purpose of this resource, and sufficient funding is needed to bankroll it.

To cater for gender and cultural sensitivities, a pool of female interpreters should be made available (as should gender-sensitive counselling).

Speaking the local language opens up job opportunities – if a migrant’s legal status allows them to work. Many arrivals are highly skilled – probably a condition of those with a temporary work visa. But still, strategies for further career development are important.

Cities could exploit this to show commitment to a just transition – a very people- and planet-friendly policy. Training programmes that retrain and upskill (unemployed) individuals in green jobs enhance their personal financial stability, as well as the continent’s progress towards climate neutrality.

Strategies should target refugees and asylum seekers specifically, especially women, as they tend to be less educated and less skilled than other newcomers (e.g. EU and economic migrants). If we want to be more ambitious, legislation could be passed that allows asylum seekers to work before they’re granted residency.

Reducing the attainment gap between migrant children and their ‘native’ classmates should be another priority. Adopting a ‘child first, migrant second’ policy paves the way to free education for all, regardless of legal status.

But school can be expensive. Even covering basic costs like providing free school uniforms relieves the financial burden on low-income families (and ensures children fit in).

Housing

Based on their studies in Stockholm, Berlin, and London, MAPURBAN points out that there’s no coordinated approach across Europe to dealing with housing shortages. Their project aimed to identify ways to improve migrants’ access to essential urban resources and participation in city society. What is clear is that planning policies should shift their vision from short- to long-term solutions, with an understanding that the inflow of new people is an inevitability.

Additionally, regulation and tenancy law can be leveraged to tackle some of the biggest hurdles to accessing suitable, affordable, quality housing, which the research projects found to be incredibly important to the settling process.

Establishing municipal ‘Solidarity Funds’ can help destitute migrants to pay deposits for accommodation and to furnish rooms. We should look beyond the practical elements at play here: one young refugee spoke joyfully of how the pictures he’d made as part of the Art of Belonging programme had brought colour to the walls of his otherwise sterile room, making him feel a lot more positive.

Fixed charges for social housing and older buildings, and constraining price increases in the private rental market, can also dispense with the causes of financial precarity.

Creating legal conditions that allow for innovation, like mutual exchange and Community Land Trusts, could be explored. (In these cases, they could protect residents from administrative or transit costs associated with moving house and rent hikes respectively.)

There should be cost transparency across the board. Municipal social housing certainly should do away with any hidden charges.

But limits can also be imposed on unreasonable up-front or additional payments, such as the estate agents’ commissions that tenants (not only landlords) are expected to pay in some countries.

Incentives work well in encouraging private landlords to open their properties to migrants, e.g. free house insurance. These also improve tenant-landlord relationships, which seems to correlate with the homeowners maintaining properties better, too.

Penalties, such as the vacancy tax used in Vancouver, Canada, and two states in Austria can prevent homes standing empty when there’s a shortage – or at least help finance the building of social units.

Obligations for landlords to properly maintain properties can also minimise tenants’ exposure to unhealthy living conditions.

Banning no-fault evictions, introducing rent caps, strengthening tenant rights – such as the ability to extend contracts, house a pet, and longer standard rental periods – boost residents’ stability and contentedness.

Planning policies that ease refugees’ transition from temporary shelters to long-term accommodation options and create decentralised housing are another move towards equal living standards.

Lund, in Sweden, has a long waiting list for housing – up to ten years! The city expedites refugees’ allocation once they’re awarded residency status by putting them on a separate waiting list from other would-be tenants. Priority lists based on precarity could be introduced as standard.

Access to quality housing links directly with a city’s climate goals. Existing examples demonstrate how municipalities can:

Less rigid building regulations and planning codes would also allow for experimentation with housing models. These could come up with new concepts that better suit migrants’ needs and help ease demand on limited social housing stock.

New financial instruments could also be leveraged to help get them off the ground.

Examples include the introduction of co-housing funding schemes shared between tenants, or green mortgages, which are gaining popularity as key government sustainability priorities – such as community cohesion and environmental protections – become de rigueur for long-term return on investment.

Local authorities and refugee bodies are advised to collaborate on lists of co-housing options. Maintaining these helps stakeholders understand the range on the market and raises awareness of availability. This resource should be easily available, multilingual, and in digital and analogue formats.

Information on forms of tenure, capacity building, and legal mechanisms such as planning regulation and new funding models can be sourced from existing communities; actors who look to international cooperation can obtain and exchange a considerable knowledge basis and use this to judge what’s most relevant to the local context.

Authorities can help by adjusting planning rules to release land to developers who prioritise positive social impact over market value.

Socio-Spatial Mechanisms

But creating better, more liveable cities is about much more than buildings – a city is the people who live there. It’s our use of that space that really matters.

Urban places have traditionally been built by men, and, in modern times, around maximising accessibility by car. Intersectionality and gender mainstreaming should be the lenses through which new planning priorities are established.

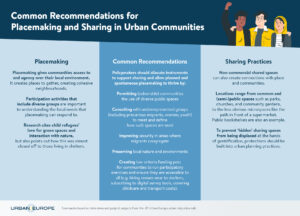

Involving marginalised groups in the creation and use of common spaces is a surefire way to support their sense of belonging. This, research has shown, is made possible via the promotion of participation, placemaking, and sharing practices.

Institutional Policies

For all the influence they have on the workings of the moving parts in a city, it’s important for local authorities to look inwards, at what needs to change in their own processes. The following mechanisms work at structural and institutional levels to aid municipalities and partners working in migrant arrival, support, and integration to mitigate discriminatory and exclusionary practices.

Public-political discourse shapes attitudes towards migrants and, in turn, this dictates how well new arrivals can integrate within a community.

Authorities should work on creating a positive, inclusive, empathetic environment, especially for forced migrants fleeing conflict or the violence and persecution of totalitarian regimes.

This can be achieved by replacing hostile language, such as ‘illegal immigrant’, with humanitarian tones; Cardiff, Frankfurt, and Vienna provide examples, having positioned themselves as cities of ’sanctuary’, ‘multiculturalism’, and ‘human rights’. They have a duty to live up to those names but – as Ilker Ataç from the LoReMi project points out – “in practice it takes committed staff and civil society organisations to make this happen, especially for precarious migrants”.

Voluntary, community, and non-governmental organisations are valuable resources on migrant issues and how to address them.

Municipal departments should implement a culture of consultation with NGOs to inform and reshape official strategies, a task that multidisciplinary teams could activate. Equal footing must be maintained: cities should not treat these groups as substitutes for essential state-funded provision but rather as experts in the field.

Precarious migrants’ lack of trust in authorities makes them hesitant to engage. They fear their data being transferred to immigration services – especially with regard to accessing healthcare – which could end with them being deported or separated from their children.

An actual lack of confidentiality is highly problematic in Germany, LoReMi have found, where sufficient firewalls are lacking. The country’s ‘expanded confidentiality’ rule does exempt medical personnel from having to inform the authorities when migrants without a regular status make contact in cases of medical emergencies. There’s an uncertainty in some departments, however (e.g. social welfare offices) where the process is less clear.

Much more successful is Berlin’s Anonymised Health Certificate, which at a local level exempts clinicians from asking for immigrant status in the first place: don’t ask, can’t tell!

These types of rules should be rolled out across the board, but it has proved to be a culture shock to some. In order for this to take hold:

Health insurance ties care to employment, preventing unemployed and low-income groups from engaging, sometimes even in emergencies. Here, the success of blanket entitlement schemes for testing and vaccinations during the COVID-19 pandemic proved how public health can be made a political priority.

Handing local authorities law-making capabilities allows cities to override the restrictions imposed by a residents’ legal status in order that they can respond to need, uphold human rights, and make good on their duty of care.

This is where a ‘migrant council’, like the one in Leipzig, Germany, can provide essential political and civic representation for migrants’ interests, communicating the needs of their communities.

But with just 7% of those eligible to vote turning out to city council elections in 2021, there is a clear chasm between holding democratic rights and using them. Bringing more migrant voices to the fore is an ongoing challenge.

Hard-hitting moves are needed to extinguish deep-rooted racism and cultural bias even within public institutions. The table below hints at how municipalities can lead the charge:

Funding Policies

What binds almost all the options discussed above is the need for money to make them a reality. But creating a positive change is not just a matter of how much there is available in the budget; it’s as much about distributing what is available more wisely.

The single greatest alteration needed in funding policy, it seems, is a shift towards long-term investment.

Cities rely on NGOs to provide the support they cannot and to act as intermediaries in engagement, but many NGOs depend on state or municipal grants, or philanthropic and public donations. These income streams lack stability. Longer-term funding commitments from authorities assure organisations and their target groups that these provisions will not just disappear. It gives NGOs a chance to properly invest in a robust and coordinated support infrastructure.

This brings us right back round to our starting point: access.

If we want migrants to make the city their own, we need to make sure they can access it – all of it. Proximity to public transport is an important step, but it must be made affordable. Free tickets for refugees is one idea; concessions like those offered by the Berlin Pass are also helpful.

But care needs to be taken to roll out these initiatives in a way that promotes equality. Young men are typically more mobile than women, children, and elderly people. Let’s not forget when we’re writing up policies that, like migrants themselves, their needs are not heterogenous.

Next Steps

An almost universal recommendation, whether expressed in final reports or during interviews, is the need to build on this research further. Project representatives call on organisations like JPI Urban Europe to offer possibilities for follow-on funding (and longer research periods) to get an even deeper understanding of the variables at play.

But also, now that this information is available to cities, it is up to them to make use of this valuable resource. The fact is that migration and the issues it raises are not likely to go away – ever! In what feels like a time of such division, acting with a sense of urgency and fairness seems the most sensible route to creating fully inclusive cities.

Note: This article is commissioned by JPI Urban Europe and produced in collaboration with CityChangers.org. CityChangers.org is a community-centred content platform for urban change-makers around the globe, created by Urban Future. JPI Urban Europe funds projects which address pertinent global urban challenges. Between January 2021 and January 2023, their support enabled eight projects to explore the concepts of urban migration and integration. JPI Urban Europe has partnered with CityChangers.org to make the findings of these research projects more tangible and accessible to a wider audience. More details about the Urban Migration call can be found on the JPI Urban Europe website.