Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

European cities are densely populated, multicultural, and full of amenities. These are some of the reasons that newcomers to a country end up in urban places. Establishing a life there should be relatively easy. But as our separate exploration of the challenges associated with migration proves, it’s not that simple to integrate.

The JPI Urban Europe-supported research projects set out many recommendations for turning this around. But before launching into action, it’s important to know what you’re acting on. This is where the tools come in handy.

All of the following tools were used by researchers, partners, or cities in the studies, or are suggestions based on findings. Not all are relevant to each place, situation, or migrant group. So to make it easier to pick through, we split them into categories: research, community-based, cultural, digital, structural, academic, and funding.

It stands to reason that this is where we start. Aside from the usual – surveys, interviews, reviews of existing research – anyone interested in learning more about migrant-related topics should consider these.

Some project teams enlisted representatives from diverse and migrant backgrounds to aid their research, with an emphasis on recruiting women.

The EMPOWER project explored the impact that community-led infrastructures and place-making strategies have on female residents’ ability to establish their (sense of) place in the city. They trained community researchers (CRs) how to conduct interviews and quantitative surveys with their peers on the projects’ behalf. This increased the rate of engagement and openness, as well as how much could be achieved in a relatively short time.

This really worked where digital surveys failed to engage an audience, and the training also formed a part of the empowerment process, upskilling CRs in:

That was actually a key component for being able to do research and to address respondents and even to conduct workshops.

Helena Cermeno Mediavilla, ProSHARE

MICOLL investigated the barriers that refugees and other migrants encounter to accessing quality and affordable housing. They also explored the potential of collaborative models to create a new institutional framework for inclusive and sustainable urban housing. This project implemented in-location practice-based ‘experiments’ “to provide ideas and examples of how refugee [collaborative housing] can be initiated, supported and sustained”.

Rather than rely on theoretic concepts, testbeds created chances for critical understanding of how variables cause local conditions, stakeholders, neighbourhoods, and target groups to react. This highlights strengths and weaknesses for potential new initiatives, designs, and strategies, which can inform future urban development and housing plans.

In the case of collaborative housing and other infrastructure-based testbeds, these structures can act as pilots – or ‘anchor organisations’ – that allow local actors to interrogate how co-housing addresses inclusion, loneliness, and cohesion. In the sustainability game, having a tangible example to show people raises enthusiasm for new concepts. And prototypes demonstrate in real terms the “socio-economic benefits for different groups, including refugees”, the MICOLL website informs us.

It’s true: results from an Austrian example influenced the formation of a National Community-led Housing Fund in England, which ties the new co-housing sector in with government priorities around health and wellbeing.

Urban Living Labs and Practices-of-Sharing Labs explore migrant experiences and migrant-adjacent conditions, e.g. policies that affect them, what local organisations exist, where they fit in to demographic and housing contexts.

These are “initiated because they contribute to a more inclusive urban development”, the ProSHARE team writes. Their focus was on how non-commercial sharing and commoning is practiced in socially mixed neighborhoods and what conditions catalyse it.

From the JPI Urban Europe projects, we are aware that labs allow long-term collaboration to form between excluded residents, local experts/professionals (e.g. social designers), and researchers that “meditate processes across different stakeholders and population groups”.

Having said that, some of these labs missed voices from those with a “long‐term immigrant background (London), recent migrants (Berlin and Vienna), and youth (Bagneux)”. Efforts should be made to ensure representation from all communities.

Whether used for acquiring localised data or creating a sense of place, instruments at the community scale can be effective in understanding and changing the way migrants interact or are affected by the socio-urban environment. They’re also a way of getting citizens involved.

Less used than labs are the policy cafes that cropped up in studies in Germany, Sweden, and the UK. As well as giving community researchers a place to link with key stakeholders, these meeting points gave migrants, among others, a chance to voice their views to those working in integration, housing, and planning.

They work like this: in a neutral community setting, people with power agree to actively listen to attendees, giving them the chance to influence local policy and strategy. For resident migrants, this is the chance to phase out the socio-spatial segregation that – like they were – future arrivals would be subjected to.

Being local and informal, policy cafes are a more inclusive access point for those willing to join participation activities but who find public meetings (e.g. in a city hall) more intimidating or physically difficult to reach (e.g. through lack of private transport).

MAPURBAN identified ways to improve migrants’ access to essential urban resources and participation in urban society. This project found that refugees often longed for safe spaces and activities they could enjoy away from sheltered accommodation. They frequently expressed interests in nature and shops.

This could be achieved through place-making. Known to kick-start community cohesion and ‘social justice’, place-making is “a key activity to help secure migrant integration in different European cities”, EMPOWER writes. Migrants especially value the personal security and intercultural events these initiatives facilitate.

Successful place-making needs to target a common value (safety, trust, acceptance) or neighbourhood identity. Superdiverse communities are ideal. The lack of a homogenous culture, race, language, etc. automatically creates a commonality: everyone is different. New arrivals also share one homogenous characteristic – their newness. This can be all it takes to create a bond. Even solidarity in the face of adversity was seen to bring people together.

In Berlin, locals were invited to map – digitally and in analogue formats – the locations of “places they experience as important for sharing and for coming together with different people”.

These kinds of insights revealed areas of abandonment, where services are sparse and ripe for improving. But they also showed how shared spaces (parks, libraries, cafes) tally with a sense of belonging, solidarity, and low-threshold access to resources.

Vienna’s temporary Garage Grande is a typical example of such a community space, where a low level of regulation creates incubator conditions for social networks, commoning practices, and peer support to blossom. Commoning, incidentally, is the term for self-governance among communities that engage in sharing practices.

This also has its place in a co-housing situation. Sharing there might extend to tutoring, cooking, childcare, and other everyday “drudgery” that can be spread among residents to “liberate the parents a little bit”, says Melissa Fernández Arrigoitia. Spaces for sharing can be built into the co-design process, including outside green spaces and playgrounds which set the scene for chance social encounters that span demographics.

Bear in mind, though, that motivation for sharing initiatives is more common among inner-city, wealthier neighbourhoods than among poorer ones in suburban areas or in social housing. Attention should be given to addressing this imbalance.

Members of a migrant’s own (cultural and language) community or ‘native’ local people are generally trusted more than the authorities. Building relationships with others who have a longstanding experience of a city can facilitate the acquisition of knowledge that arrivals need to navigate their new surroundings and the systems that govern it.

References to ‘buddies’ occurred in a few of the projects. The Art of Belonging used creative tools and participation in cultural placemaking to investigate the relationship between art and social integration for young forced and unaccompanied refugees. This project intended to test the idea of buddies, but COVID-19 restrictions prevented the possibility. Still, the informal peer support that formed naturally was enough to show how buddy systems have a positive impact for newcomers.

The HOUSE-IN project assessed the impact that innovative, inclusive housing strategies have on migrant integration, identifying the gaps and how to stimulate co-creation to fill them. Their report makes reference to a buddy programme run by the church-led Diakonie Flüchtlingsdienst GmbH (Wohnen in Wien für Asylwerber*innen und Flüchtlinge) in Vienna. This supports forced migrants with housing issues (advice, searching, tenant laws, etc.) staffed weekly by volunteers – the ‘Wohnbuddies’. This works well because support is offered in a range of languages, including Arabic, Farsi, and Somali, and German.

But volunteer-run and faith organisations can’t do much to solve structural discrimination. If anything, by filling gaps in official services, they divert attention away from institutional deficiencies. To make amends, cities could offer these services but in a formalised capacity, staffed by professionals. MICOLL also advises co-housing groups nominate buddies among residents to help new-joined refugees get to grips with the living environment and host culture.

Identity is built around culture. So, it figures that a change of cultural surroundings upsets our sense of identity. To make the process an easier and more enriching experience, some tools can be employed to help form new cultural connections as part of the integration process.

Rather than seeing a person’s worth based on labour-market potential, The Art of Belonging project viewed participants’ experiences through a social lens and helped them to fill a Cultural Rucksack.

This is a metaphorical concept, in which participants were guided in forming their own cultural citizenship – a sense for being part of the local cultural landscape. Invited to a programme of activities at different artistic institutions, young refugees were supported to develop an understanding of the culture of their new city through artistic expression.

When creating alongside others, young people exhibited feelings of security, allowing them to open up about past traumas – which the group leaders were careful not to instigate conversations about unless promoted – in a demonstration of ‘art as therapy’.

Practical activities led to skill development and were designed to engage participants regardless of language barriers, proving extremely popular.

Key learnings from running this programme include the need to:

The project has a public repository of readymade art workshops for use in the Cultural Rucksack.

Talk of sustainable cities is ablaze with tales of the capabilities of artificial intelligence. In the realms of urban migration this ranges from number crunching data on mobility patterns to helping us meet Sustainable Development Goals (primarily number 11, if you were curious, just like all eight of the JPI Urban Europe research projects). But there are a handful of micro-scale digital tools that cities are already turning to in order to learn about or support local migrant populations.

Smartphones are ubiquitous. For forced migrants, it may be the one personal item they arrive with, packed with photographs from home, voice messages, translation apps, etc. The Art of Belonging’s participants used theirs for acts of community-building – sharing images and videos of culture, nature, and food from their native countries.

Future programmes of arts and cultural activity should harness this and recognise and build on the potential of mobile phones in the planning of sessions.

Art of Belonging

The ProSHARE team on the other hand somewhat dismiss the extent of praise lauded on personal digital technology, with particular reference to the elderly and less affluent.

Rather, the most powerful mechanism in organising sharing activities among communities is personal contacts – friends, family, neighbours. And the more sharing that is visible, the wider the net is cast – to acquaintances and even strangers.

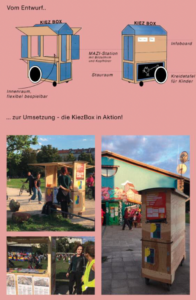

It’s a different story with mapping tools. The ProSHARE Labs in Paris and London used Gogocarto, and in Berlin they integrated Adhocracy and MAZI. The latter was built into a temporary mobile intranet station. In the Kiezanker 36 neighbourhood, local residents were asked to record media or complete a survey relating to their community and its experience with sharing. It also allowed researchers to share information with the populous and to consolidate it with external media and analogue data.

The downside is that, to work well, it was found to need a (hired!) programmer to adapt and maintain the open-source software. This takes quite a lot of time as well as finance.

But maps, whether digital or analogue are useful. MAPURBAN tells of a successful collaboration between Sweden’s Health Department and the Stockholm Region administration, which independently mapped public transport links to clinics and hospitals. Where “previously the location of the facility had seemed rather irrelevant”, the analysis revealed that it actually correlates with poor access. Further socio-spatial analysis demonstrates how ticket prices still exclude people from poorer neighbourhoods even when well served by subways and buses.

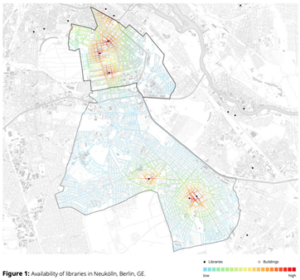

The map below showing proximity to libraries in the Neukölln area of Berlin – as an example of a public provision and centre for social mixing, learning, and culture – is a powerful visual reminder of how urban planning can underserve certain neighbourhoods. All too often, they’re the poorest areas.

All too often, migrants can fall through institutional gaps. An inclusive city is one that ensures this does not happen, regardless of someone’s legal status. Structural tools seek to mitigate these exclusions.

The introduction of municipal multidisciplinary teams facilitates inter-departmental knowledge-sharing and cooperation. This, observed cases suggest, is effective in bridging gaps, notably in legal issues, and clarifying signposting processes to link migrants to relevant support.

Authorities can mobilise these teams, which audit local provision by coordinating with city stakeholders (e.g. migrants, NGOs, housing providers, advice agencies). As LoReMi reports, it’s important to publish clear, up-to-date information about entitlements, access requirements, and training opportunities. They ascertained this from their project while looking specifically at the needs of precarious migrants, with the aim to strengthen local strategies to address exclusion from essential services.

Melissa Fernández Arrigoitia from the MICOLL team suggests that cities can introduce property guardians to open up new locations to house migrant groups.

Property guardians are, she explains, “unusual buildings owned by local authorities” that people normally do not inhabit, like abandoned pubs and churches. Private organisations maintain them.

In an agreement that offers few amenities, rights, and securities, property guardians license the building to those who wish to occupy it because it offers more space than a flat, and very low charges. It’s a little mentioned form of co-housing.

Picking out what needs to change and then doing it – at however small a scale – is a process. This is where the academic contingent of the JPI Urban Europe project consortia excel. Two stand-out methods arose in the research: a Theory of Change, and Transition Management.

EMPOWER’s research culminated in a Theory of Change framework. It’s a process that “explains how and why a desired change is expected to occur in a particular context”.

In essence, this states the problems, suggestions for activities, the expected outputs, and the indicators that measure their impact. By assessing the results, we know whether the change has worked, whether it should continue, and what we should tinker with.

This is not a new idea, but the fact that it’s still practiced gives some indication of the effectiveness of such a tool. And like EMPOWER’s version, it can apply emphasis to a particular set of challenges, in this case by applying gender-aware and gender-sensitive approaches to form strategies designed to improve equality.

A related but different approach is that of Transition Management, a tool that puts stakeholder participation at the centre of the design of transition activities.

The three-fold process is to 1) understand the complex problems presented in a community, 2) bring stakeholders together to collaborate on a ‘transition agenda’, and finally 3) co-design operational activities and experiments to see what works and what we can learn from trying.

MICOLL found this particularly effective in capacity building and the scaling up of collaborative housing models.

It goes without saying that many of these tools in one way or another can only be implemented if there’s enough capital to get them off the ground. Even community researchers should be compensated for their time – it improves long-term commitment. But because so many services are underfunded, money itself can be used as a catalyst, and therefore it deserves a mention as a tool in its own right.

From providing language courses or anonymous healthcare to initiating new housing provisions, channeling funding in the right direction would improve what’s on offer for the benefit of all marginalised groups, not only migrants.

This should be targeted to need, though, and put in place with the input of residents and local stakeholders. Mapping in Paris unveiled how continuous funding from municipalities increased the presence of organised sharing activities. But it also led to competition among groups fighting for limited resources, which undermined chances to create the mutual support it was intended for. Spontaneous activities run by volunteers are much better at that, but few can commit to it full time. Capital injections can bring the benefits of both together.

Inclusive Housing researched what obstacles refugees and other disadvantaged migrants encounter when trying to access long-term housing, including local housing types, market, and governance. Their report identified that financial mechanisms like a municipal Solidarity Fund can be a great tool for promoting “decent housing and living situations”. Not only does it focus on financial aid, but such a fund can help foster awareness of, empathy for, and solidarity between different actors in society. That sounds like a great basis for integration.

Next Steps

This is not an exhaustive list, nor is it prescriptive for what works at every local urban level. What this selection of tools does prove is that European cities and research projects have a wealth of options at their disposal.

It’s important to approach them critically before implementation to ascertain their relevance, and again – both during and after the process – to evaluate results. All being well, though, these tools can provide the foundations for improvements at the municipal level. That knowledge will enable urban actors to select the right levers for change – many of which can be found in our recommendations guide.

Note: This article is commissioned by JPI Urban Europe and produced in collaboration with CityChangers.org. CityChangers.org is a community-centred content platform for urban change-makers around the globe, created by Urban Future. JPI Urban Europe funds projects which address pertinent global urban challenges. Between January 2021 and January 2023, their support enabled eight projects to explore the concepts of urban migration and integration. JPI Urban Europe has partnered with CityChangers.org to make the findings of these research projects more tangible and accessible to a wider audience. More details about the Urban Migration call can be found on the JPI Urban Europe website.