Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

“Traditional transport planning was forecast-led and traffic-focused,” explains Lyons. “And whilst it gave a nod to uncertainty, it hasn’t really taken seriously the idea that we can’t predict the future or even forecast a likely future.”

The Evolution of Transport Planning

To understand the significance of TAP, it’s crucial to consider the evolution of transport planning. As Lyons points out, the discipline is relatively young compared to fields like civil engineering. It gained formal recognition in the 1960s, when cost-benefit analysis for transport infrastructure was starting to be taken seriously.

“We went through an era where the motor car arrived, and it seemed like a jolly good thing for society,” Lyons reflects. “And so, we started to develop ways of working out how we could build more roads to accommodate the growth that was expected and wanted in people’s access to the car.”

This led to what Lyons calls the “predict and provide paradigm”, where planners would forecast traffic growth and then provide infrastructure to accommodate it. However, this approach has led to unintended consequences, particularly in urban areas.

“We’ve invited the car into society in such an extensive pervasive way. Whilst some of its benefits are still very apparent, and many of us, myself included, enjoy access to using a car, it’s created all sorts of negative externalities, including, of course, carbon dioxide emissions, intrusion into urban environments, and the loss of space and a sense of place for community” Lyons explains. Triple access planning invites greater consideration of the role of digital connectivity and spatial proximity, that may lessen our dependence on cars and thus reduce some of their harmful impacts.

Connecting the Dots: The Triple Access System

At the heart of TAP is the recognition that accessibility—the ability to reach needed or desired goods, services, and opportunities—can be achieved through physical mobility, spatial proximity, or digital connectivity. The project brought together partners from five countries, including universities, city authorities, national governments, and consultancy firms, to explore this interconnected system.

The team undertook a series of eight systems thinking workshops to help stakeholders co-create a mental model of the triple access system as a basis for understanding and applying Triple Access Planning. This approach gives planners a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing urban mobility and accessibility. “Before you can plan how to shape a system, you really need to understand what system you’re trying to shape,” Lyons notes. The series of workshops involved representatives from all project partners, including academic institutions, city authorities, national transport agencies, and consultancy firms. This diverse group of stakeholders ensured that the resulting system diagram captured a wide range of perspectives and experiences.

Preparing for an Uncertain Future

Recognising the inherent unpredictability of the future when undertaking long-term planning, the project developed six possible divergent future ‘triple access’ scenarios.

“There are so many things in a state of flux in the world now, socially, technologically, economically, environmentally and politically, that traditional transport planning isn’t really giving our decision-makers necessarily the best advice in terms of how we provide stewardship over the future,” Lyons emphasises.

To complement the scenario development, the team conducted an extensive review of 37 existing Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMPs) and local transport plans across Europe. This review aimed to identify gaps in current approaches and opportunities for improvement.

“What we discovered broadly was that there wasn’t much recognition of uncertainty in these plans and really very little consideration of digital connectivity,” Lyons reports.

Bringing TAP to Life

To give planning stakeholders first-hand experience of TAP, the project implemented “FUTURES Relays” – intensive two-part workshops designed to take participants through the TAP process in just four hours. These were conducted in several European cities, including Nova Gorica in Slovenia, Cagliari in Italy, Aberdeen in Scotland, and a citizen-focused event in Bristol, England.

The Bristol event was particularly noteworthy, engaging 30 members of the public over two Saturday mornings. “We wanted to engage the public,” Lyons explains. “We were very keen to try and draw out as much diversity as possible. Not just hearing from white male transport planners.” Those taking part were reminded of the role of proximity to things they need and the possibility of digital accessibility in support of their activities, alongside the more familiar emphasis on transport. Triple-access was recognisable to participants though not necessarily as readily discussed as the well-rehearsed frustrations about transport.

One of the project’s most innovative outputs is a serious game that introduces TAP to practitioners. Throughout the project, about 40 teams played it across various settings. The game challenges its players to weigh up the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of adopting TAP in their own contexts. The game consists of 40 playing cards representing different aspects of TAP, which players must prioritise and discuss. It’s available both as a physical card game and in a digital format, making it accessible to a wide range of users.

A Handbook for the Future

The culmination of the project’s work is a comprehensive handbook on Triple Access Planning. Designed to be both thorough and accessible, the handbook guides practitioners through the philosophy, process, and practical application of TAP.

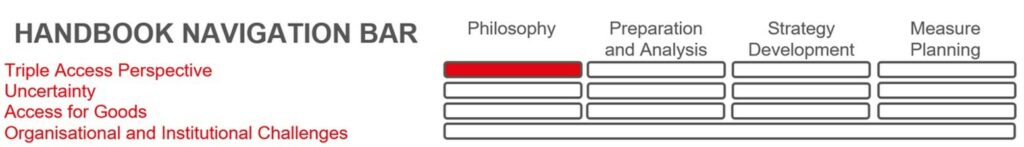

“We put a lot of thought into this,” Lyons explains. The handbook is structured around four planning phases: philosophy, preparation and analysis, strategy development, and measure planning. These were represented by four columns. It also addresses four key dimensions of TAP: the triple access perspective, uncertainty, access to goods, and organisational and institutional challenges. These dimensions were arranged in four rows. Lyons explains, “the idea is that there will be some people who we call column readers or row readers.” “You might come to the handbook and think, I don’t want to read the whole thing, but I’m interested in access for goods. What do they, what does this handbook say about goods? So, you can look along that third row and you can go across the planning process for just that.”

To increase accessibility, the team also produced a 10-page summary version of the handbook, which has already been translated into all five languages of the project partners, as well as French and Spanish.

Early reception of the handbook has been positive, with interest from organisations ranging from the National Infrastructure Commission for Wales to the UK Department for Transport.

Changing Mindsets, Shaping Cities

While the TAP for Uncertain Futures project has made significant strides in developing and promoting a new approach to urban planning, Lyons acknowledges that widespread adoption will take time. “Change doesn’t happen overnight,” he says. Lyons emphasises that the journey towards TAP has been a decade-long process, starting with his work in New Zealand and continuing on in this project. “Triple access planning has been applied in South Africa. It’s been applied in Australia, as well as being applied in the UK,” he notes. He adds, “you have to keep nurturing this diffusion of innovation. You have to keep championing it and encouraging a community of practice to grow.”

As cities worldwide grapple with the challenges of climate change, technological disruption, and shifting social norms, the TAP approach offers a flexible, forward-thinking framework for creating more resilient and accessible urban environments. By considering the interplay between physical mobility, spatial proximity, and digital connectivity, planners can develop strategies that are better equipped to navigate an uncertain future.

The TAP for Uncertain Futures project demonstrates that effective urban planning in the 21st century requires a holistic approach that goes beyond traditional transport considerations. As Lyons puts it, “I’m not saying that I don’t think people should go outside their houses anymore and that they should predominantly live in front of their computer screens. This is about saying that we’ve got this triple access system, which means we’ve got three different systems providing the supply side that gives us a choice about how we go about our lives in terms of the demands that we place upon it.”

With the tools and frameworks developed by this project, urban planners and policymakers now have a comprehensive resource to help them navigate the complexities of modern urban mobility. As the concept of TAP continues to gain traction, it has the potential to reshape our cities, making them more adaptable, sustainable, and making the most of our new digital age.