Join JPI UE

Faq

FAQ

Please click here for the frequently asked questions we collected.

If you have an additional questions you are welcome to mail us at info@jpi-urbaneurope.eu

Shelter is a basic need.

Safe, stable, accommodation that’s of a decent standard, and provides comfort and more than just fundamental amenities, is a foundation of integration.

A reliable place to live – or even call home – eases access to education, employment, and medical care. It facilitates simple day-to-day necessities, like setting up a bank account, and helps migrants navigate local bureaucratic systems, the language, childcare, and social interactions, and ultimately hands them autonomy.

Even though in Europe housing is considered a fundamental right, we’d be wrong to assume that everyone can access it equally. Multiple factors hamper migrants’ prospects on the housing market:

One of the most unsettling features of urban housing for migrants is the lack of long-term solutions. This was highlighted with crystal clarity when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine displaced 8 million people, most of them arriving in cities elsewhere in Europe.

Growing Tired of Short-term Solutions

“In Poland, Austria, Germany and Latvia, as in other countries, people have opened their homes, marking a show of solidarity and care,” writes Giovanna Astolfo on the European response to the Ukrainian refugee crisis.

Interventions driven by compassion may work initially, but after just four months there were signs that ‘compassion fatigue’ had set in. Once again, these refugees were at risk of homelessness.

As such, research by the HOUSE-IN project – which assessed the impact that innovative, inclusive housing strategies have on migrant integration – sets a scene whereby “short-term fill-the-gap strategies” are insufficient for housing precarious migrants.

In fact, this level of solidarity undermines the universal right to safe housing. There’s also the risk that sustainable solutions will be depoliticised – deflecting the responsibility for care away from the authorities. In the face of a housing shortage, the need for official and coordinated responses must stay firmly on the political agenda!

Civil society organisations, Giovanna adds, are calling on “state institutions to play a stronger role” in creating housing strategies that meet the needs of vulnerable migrants. But as research supported by JPI Urban Europe shows, the solutions really require the cooperation of multiple actors, a culture shift in the housing market, and a true understanding of the issues we’re dealing with.

The Most Basic Accommodation

Urban Living Labs revealed each city to contain housing in a state of disrepair. Undesirable to local tenants, in some cases this is used instead as emergency accommodation for forced migrants. Plans to improve the quality of these properties faces opposition as locals fear it will bump up their own rents.

So, where do they go? Slipping into homelessness is a very real danger for vulnerable migrants.

Homeless assistance at least protects the most destitute from harsh winters. From city to city, however, gaining access to emergency accommodation sometimes depends on legal status. Cardiff, in Wales, provides bed space in shelters to asylum seekers in exceptional and humanitarian circumstances, like periods of recovering from surgery. But this is the exception. The research shows that precarious migrants are generally excluded from emergency accommodation, except where this contradicts a legal duty to prevent acute risk.

Those with a more stable legal status aren’t off the hook either! Larger families struggle to find affordable places big enough, as social flats tend to be built to a standard size.

As a result, Inclusive Housing explains, migrants gravitate towards substandard options, where “they struggle with unhealthy and overcrowded housing conditions, legal uncertainties and often high rental costs”.

Marginalised groups find themselves squeezed out of a financialised and commodified private housing sector where those who can pay get priority.

Many migrants tend to belong to low-income households, which are generally restricted to substandard quality housing. As a much more affordable option – subsidised by municipalities – social housing is lauded as a solution. But still, it’s possible for poorer households to spend a bigger proportion of their income on housing than higher earners. Increasingly extreme weather conditions and rising energy prices – exacerbated by the Ukraine/Russia war – occasionally push utility costs to exceed rent, creating a perfect storm of economic exclusion.

Having scant personal social networks confound migrants’ chances of finding anything independently, anyway, so newcomers rely heavily on municipal or NGO support for flat hunting – if this service exists!

As if this isn’t hard enough, the competition for accommodation causes social tensions too, with some people even putting the blame for housing shortages on migrants in the first place.

While that’s hard to prove, it’s true that Europe’s population is rising, and that migration adds to demand.

In response, the continent is building. The problem, if the Swedish cities of Lund and Helsingborg are any indication, is that high construction costs can lead to rent discrepancies, trapping low-income households in older, poorer quality properties.

EMPOWER – a research project that investigated the impact of community-led infrastructures and place-making strategies in superdiverse neighbourhoods – notes that poor quality and low maintenance of housing infrastructure can undermine migrants’ attachment to a place.

They also observed a self-imposed (or ‘internalised’) stigma of shame felt by asylum seekers based on their status.

This shame prevents them from mixing socially or “encountering locally rooted people”, which has a “pronounced impact on the integration process”. So too does the uncertainty of their long-term housing prospects.

Refugees and asylum seekers are usually assigned to shelters, which is more a policy of detention that protection.

Consisting of very basic, often shared rooms, with limits on visitors, tight security, and strict rules for residents, these shelters are not intended to be an ongoing arrangement.

MAPURBAN set out to identify ways to improve migrants’ access to essential urban resources and participation in urban society. They saw asylum seekers stuck in hotels not suitable for long-term accommodation, usually because underfunding limited onward options.

Vienna, however, was shown to take a unique approach. The city offers 600 private rooms in ‘opportunity houses’ (Chancenhäuser), which combine accommodation with support from counsellors to help find their next place. The rooms are mainly designated for men, but some are suitable for women, couples, and families. As they’re available for stays of up to three months, this gives migrants some mid-term stability. However, spaces are more likely to be offered to people with better prospects of finding other accommodation (i.e. EU citizens) over precarious migrants – and it can be up to the discretion of staff who is let in at all.

It’s a similar picture for survivors of domestic abuse and human trafficking; migrants struggle to find spaces in refuges and safe houses more than local women.

Access to any support, though, depends on precarious migrants being ‘visible’ – known to authorities – which they may try to avoid.

The research shows few firewalls exist to prevent the transfer of personal data of precarious migrants accessing housing support and emergency shelters to the authorities. Fear of engaging for this reason leaves them ‘voluntarily’ excluded from statutory support entirely.

That pushes individuals towards the private housing sphere – especially the ‘grey’ or short-term rental market – where racism or opportunism is more likely to creep in.

Migrants tell of paying more than ‘native’ tenants or landlords who demand rents months in advance because of assumptions they’ll struggle to pay – discourtesies locals are not subject to.

This mistrust seems to be based on language barriers and perceptions of poverty, prejudices about a migrant’s status, race, or nationality, cultural stereotypes (e.g. noisy, staying up late, smells), or assumptions based on names and accents. Migrants report being passed up on suitable housing in favour of longstanding locals because, as landlords claim, their presence would make other tenants unhappy.

EMPOWER writes of female residents being restricted to a limited pool of housing because of their skin colour or ethnic background, as well as being charged “over the odds for substandard accommodation”.

Evidence shows that bias in housing is systemic, too, as exemplified in Berlin, where housing associations only publish information in German. Language remains a persistent block to understanding the local market and navigating heavily bureaucratic application processes.

A Nod to the Solutions

Connecting those living precariously with diverse housing options is essential to creating cities characterised by inclusion, cohesion, and responsiveness to those most in need.

As we strive to develop better, fairer, more sustainable cities, housing must be at the centre of discourse. That’s why Gopal Dayaneni is quoted as saying, “In a Just Transition… [w]hat we’ll be giving up is precarious housing”. Put another way: as we change the way we build in order to create liveable and net-zero cities, we have the chance to design-in inclusivity, comfort, energy efficiency, and equality from the ground up. We could even upskill and employ new arrivals in the green industries, allowing them to contribute to climate goals as fully integrated members of European society.

Many of the JPI Urban Europe research projects put forward solutions linked to the problems discussed here.

The types of housing options localities choose to build and offer their resident populations make a big difference to migrants’ experiences.

Housing centrally affects the wellbeing of those newly arrived.

MAPURBAN

While it is not likely the solutions outlined here can be duplicated as-is, with adaptation to local conditions they do provide a robust template for positive, sustainable change. Some examples also shed lights on what we should avoid.

For a comprehensive look into what local authorities and migrant-adjacent actors can do on a policy and structural level, check out our separate reference guide for housing market mechanisms.

Other than improved affordability through subsidisation, the main feature of social housing is that occupancy and rents are regulated. This safeguards accessibility and security for disadvantaged groups.

Even so, many municipalities ringfence provisions based on residency status or permitted length of stay, which, alongside conditions of income and nationality, creates barriers for refugees and precarious migrants.

Building regulations and laws that govern land use are important mechanisms in the creation of subsidised housing. A city can also use these, along with conditions written into contracts with developers, to push forward their demands on quality and types of building stock and the construction of affordable housing.

Migrants don’t seem to stop moving! The research found only half remained in one neighbourhood for up to a decade or more. Many go to other parts of the city to be nearer people or communities who share their language, culture, or beliefs. This form of ‘voluntary segregation’ is referred to as chain migration.

The Gothenburg municipality, in Sweden, has made efforts to encourage resident retention. They set out to improve living conditions, mainly in the poorer area of Bergsjön, by constructing new detached and semi-detached housing. But absentee landlords viewed this more desirable (i.e. gentrified) neighbourhood as a reason to raise rents, which brought criticism from local stakeholders.

Similar fears over gentrification in Leipzig, Germany, led the city to restrict the modernisation of existing housing stock. They implemented a conservation policy, preventing properties from being turned into luxury flats, effectively keeping rents more affordable but standards lower.

A challenge is to develop and renovate property in a way which meets the needs of residents, and which is affordable.

EMPOWER

The Inclusive Housing project researched what obstacles refugees and other disadvantaged migrants encounter when trying to access long-term housing. They report how Austria, Germany, and Sweden have tried to diffuse competition for housing between refugees and other low-income groups with the introduction of modular homes.

Modular housing can be erected quickly and – theoretically – serves as emergency accommodation during future crises. But they are also lower quality than permanent structures and less suited to long-term occupation. Plus, other low-income groups like students find them desirable too, keeping competition for spaces alive.

Then there’s the other quandary: they have to go somewhere! Empty tracts of land are usually only found on the periphery of a city.

Placing people in purely residential areas on the outskirts of a city, where land and rents are cheap and inhabitants are distanced from the other connections they need, is a form of forced, or “state-sponsored” segregation. This is typical of refugee accommodation, which tends to be clustered “close to socio-economically disadvantaged” neighbourhoods.

In fact, this is a recipe for ‘ghettoisation’ – the segregation of a homogenous group – and it is neither conducive to equality nor “networking opportunities or community support”, writes EMPOWER.

MAPURBAN is an advocate for “decentralised housing solutions with equal living standards”.

Decentralised housing allows migrants to sublet designated flats from the municipality (often leased from private owners) that are mixed in with the local population. This is intended to encourage social encounters to occur naturally, enhancing integration.

It is also said to improve mobility, but spreading refugee accommodation around the city can still put them “quite far from the city centre”. This means residents have longer distances to travel to access work, language courses, childcare, etc. And they may not have enough cash to make use of public transport.

This has repercussions for people’s sense of place.

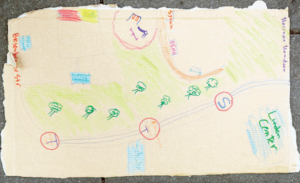

MAPURBAN ran a two-day workshop in Berlin, which picked up on the impact of decentralised accommodation on refugee women and children. Asked to draw a map of where they live, those from local shelters only depicted their direct vicinity and spoke of restricted movement caused by stringent security.

Children living in decentralised housing, however, drew their friends playing in the public places where they meet. Their mothers also had a wider perspective of the city, but their maps revealed how their refugee status still has implications: they had little knowledge of enriching public infrastructure like libraries and leisure centres.

Social mixing also does not protect newcomers from institutional racism, especially in superdiverse communities.

One of the studies focused on how non-commercial sharing and commoning is practiced in socially mixed neighborhoods, and what conditions enable it. ProSHARE reports how Uppsala’s neighbourhoods are dubbed as ‘vulnerable areas’ (utsatt område) by police based on stereotypes. They believe “organised crime, low income, low education, high unemployment, [and] dependence on welfare” to be prominent among migrant populations.

Housing that is most responsive to the diverse needs present in a city requires input from the residents themselves.

Yet few places were deemed to offer the local structures needed as a foundation for participation or co-creation processes. Used correctly, these promise innovative options which better serve migrants’ needs.

This we know thanks to another two projects: MICOLL, which addressed the barriers to quality and affordable housing for refugees and other migrants; and LoReMi, which looked specifically at how precarious migrants are excluded from essential services and accommodation.

Mainstream housing sectors insufficiently cater to the needs of people with migrant and especially refugee backgrounds.

MICOLL

One choice that seems to be gaining in popularity is collaborative housing. In a nutshell, this is a model “in which residents rent complete apartment units and share kitchens, dining areas, and other spaces”. This set up allows and encourages residents to socially interact on a daily basis and normalises diversity within a community, which supports the integration of newcomers.

The affordable SällBo (Companion Housing) initiative from Helsingborgshem, Sweden, is a typical example. There, young migrant (and local) adults live together with pensioners as a means of mitigating poor social and emotional wellbeing, such as the loneliness these groups are inclined to feel.

With new co-housing developments, there’s an option to involve potential residents in co-design at every stage. Giving vulnerable people an equal voice in the development of a home empowers them (alongside other residents) to shape diverse room sizes, creating common in- and outdoor facilities, and manage daily activities. These features help ensure that properties respond to diverse needs and cater for cultural (e.g. cooking) habits.

Inclusive Housing found many insights into the role of private rental markets and how these “can and should contribute to more inclusive housing”.

The Private Rented Sector Leasing Scheme Wales, for example, allows homeowners to rent out their properties to the local authorities, so they can house destitute locals and migrants – adding to the stock of decentralised housing.

Initiatives like this can even make use of empty properties where social housing and other forms of accommodation are scarce.

Whatever type of accommodation someone lives in, it has a vast knock-on effect. Research has identified that an address is required to register for health services and secure a job. Vienna responded to this challenge by setting up a smart housing programme to get people off the streets and into small but low-rent flats.

The concept is that, if someone has a stable home, they have a pathway to meeting all their other needs – such as access to all-important language classes, employment, a bank account, education, healthcare, and socialisation.

Next Steps

Although each of these solutions has its problems, having a roof over ones’ head is better than the alternative. Despite the myriad issues at play, there are plenty of options available for cities to choose from – and a diverse mix is certainly likely to appeal best to (super)diverse populations. It’s now up to decisionmakers to collaborate with the full range of stakeholders active in housing and migrant issues to implement these to the best of their ability.

To get urban actors started in their journey to building a better housing sector, we’ve put together a comprehensive guide to policy recommendations and support mechanisms. Why not make it your next stop?

Note: This article is commissioned by JPI Urban Europe and produced in collaboration with CityChangers.org. CityChangers.org is a community-centred content platform for urban change-makers around the globe, created by Urban Future. JPI Urban Europe funds projects which address pertinent global urban challenges. Between January 2021 and January 2023, their support enabled eight projects to explore the concepts of urban migration and integration. JPI Urban Europe has partnered with CityChangers.org to make the findings of these research projects more tangible and accessible to a wider audience. More details about the Urban Migration call can be found on the JPI Urban Europe website.